On Wednesday I posted a piece entitled “Cryptid Epistemology,” which was more about academics’ desperate attempt to monopolize “truth” through a campaign against “disinformation” more than it was about searching for Bigfoot. That said, the two topics are intertwined, and the piece is an exploration of why access to information, and the ability to parse and analyze that information, is so important.

What I admire about the more humble and intellectually honest side of the cryptid community is that they are open to the possibility that we don’t know everything. Indeed, they carefully sift through thousands of hours of footage, interviews, blog posts, books, etc., in search of gold. That they often come away with pyrite does not discourage them; instead, they keep looking, gently setting aside the few nuggets they find for further evaluation.

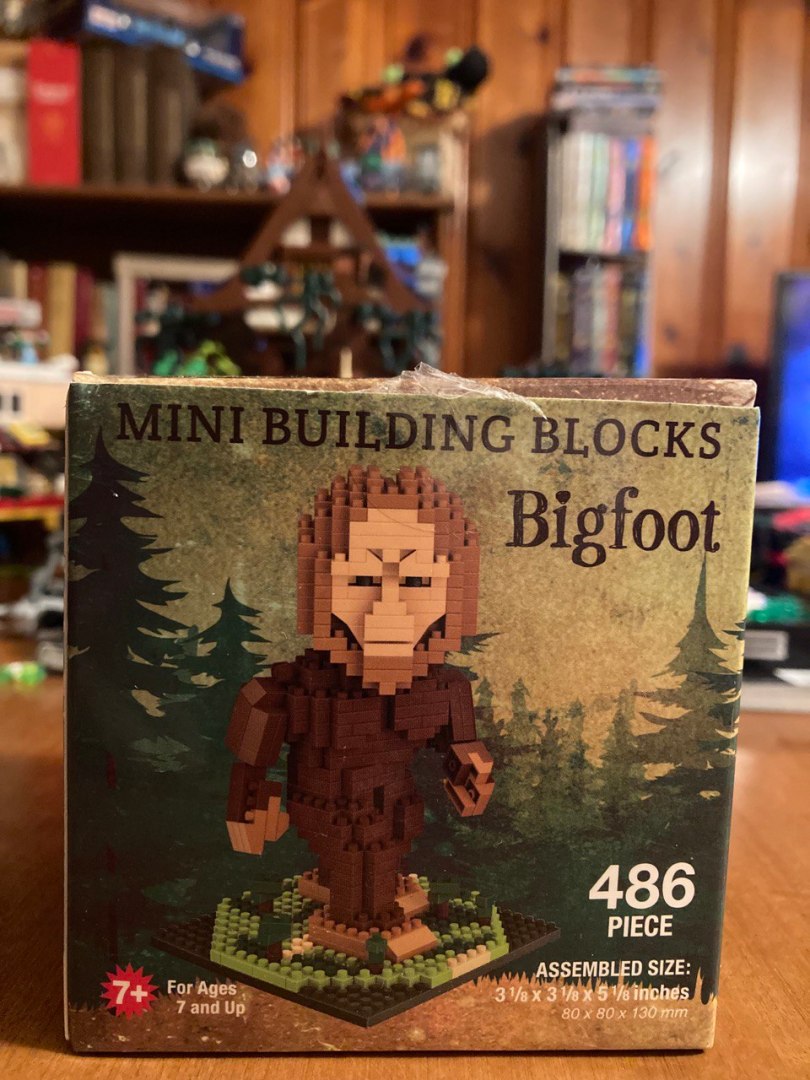

Maybe Bigfoot exists—maybe he doesn’t. What’s important is that these folks, so often dismissed as kooks, are sharpening their minds and engaging in intense analysis of thousands of data points. They are making healthy skeptics of themselves, even as they search for something at which most skeptics would scoff.

Who, I ask, is the real kook? So many self-proclaimed “skeptics” are merely parroting the very same narrative that was spoon-fed to them in a high school history class, or in their freshman philosophy course at college. They often do so with an air of condescension and derision, the sort of know-it-all-ism that derives from an excess of education but a dearth of wisdom.

The older I get, the more I realize how precious little any of us know. Things that were taught to me as inerrant “truth” have turned out to be a vast panoply of lies and half-truths, assembled into a shambolic, Frankensteinian mess for the benefit of the government and corporations.

To give one rather benign but illustrative example, before I turn it over to Audre Myers: as a kid, my elementary school teachers would, it seemed to me, forcefully and a bit angrily insist that the United States was moving to the metric system, and we’d all need to learn it so we could cope in a post-Imperial units world. It was all nonsense, and even as little kids we all kind of knew it was a bit overblown. Had our teachers said, “the metric system is important to learn because it is the standard in scientific research,” it would have been a.) truthful and b.) productive. Instead, they tried to terrify us into thinking we’d all be European, holding our cigarettes like gay men and speaking Esperanto (yes, another lie they told us in elementary school).

To be fair, things that I have taught have turned out to be inaccurate. The more I study history, for example, the more I realize that the narratives I teach—often derived from what my history teachers taught me—are often incomplete or even incorrect. When teachers talk about creating lifelong learners, it is for a reason: we can only get a small fraction of the Truth in our lives, and we should constantly undergo a refining process to purify our knowledge.

But I have overstayed my welcome in this overly long introduction. Audre offers up an excellent continuation of “Cryptid Epistemology,” her own further refinement on the journey towards Truth:

Read More »