Science fiction is amazing. When it comes to fiction, it is probably my favorite genre, second to (but rivaling) only the ghost story. Science fiction is a form of speculative fiction, which—as the name suggests—speculates about future events.

But the best science fiction doesn’t just look into the future—it tells us about ourselves, past, present, and future. That so much of the great science fiction of the twentieth century has come true, to one extent or another, is indicative of the power of the genre to diagnose social developments, if not to predict them precisely.

The latest uproar over artificial intelligence—and the apparent willingness, blind or intentional, to develop it beyond all sensible precautions—is a prime example of the failure to take the warnings of science fiction seriously.

Science fiction is not Scripture—far from it!—but we ignore its warnings at our peril.

I recently attended an annual used book sale in my hometown of Aiken, South Carolina, with my mom. While she loaded up on Maeve Binchy and the like, I pawed through the faded, yellowing science fiction paperbacks. At a quarter a pop, I was like a kid in a musty candy store. I loaded up on quite a few obscure titles, and am slowly making my way through the small stack.

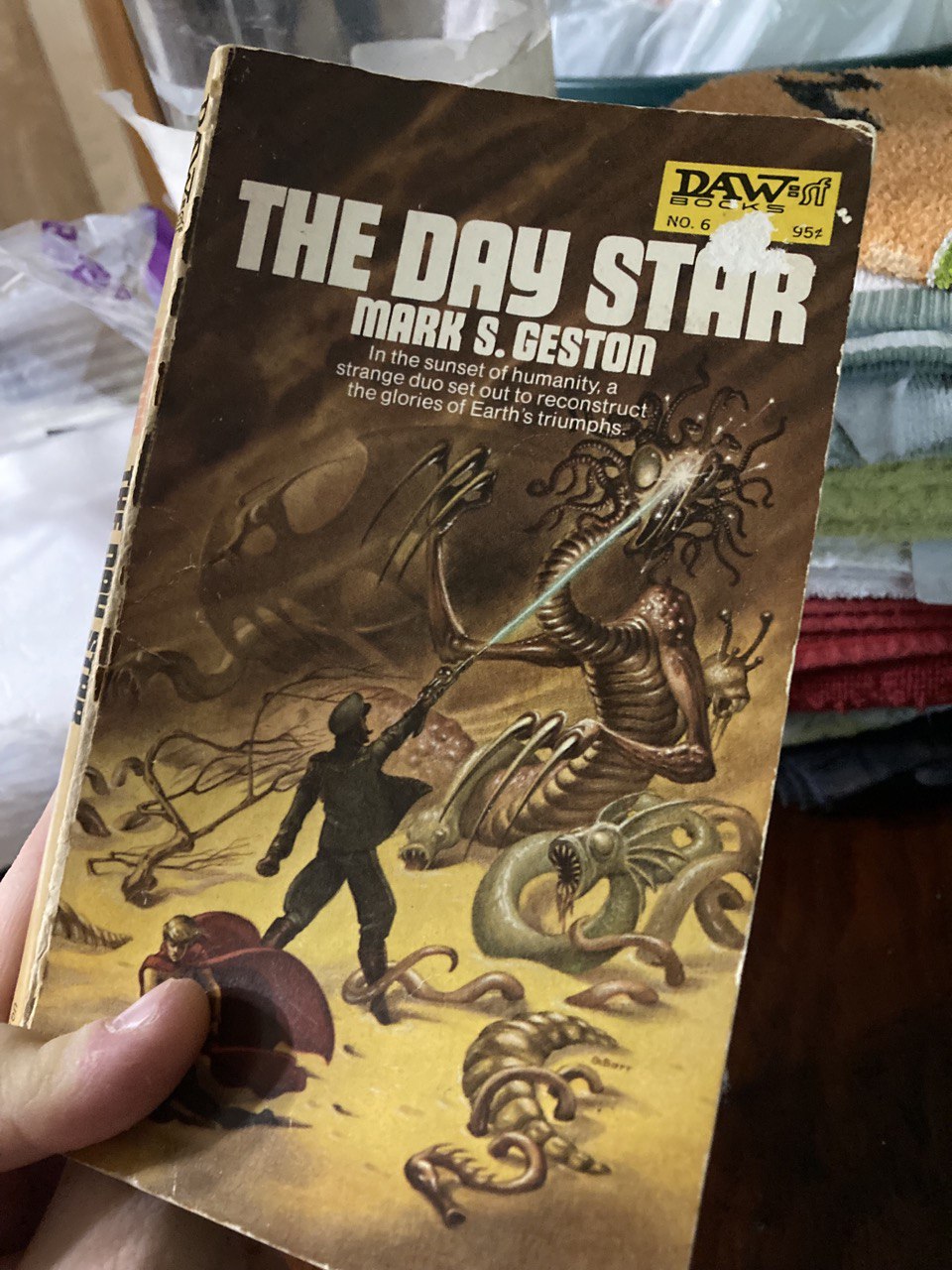

The first book I read was The Day Star by Mark S. Geston, published in 1972 by DAW Books. I picked it up in large part because of this outrageous cover:

That cover depicts one very brief scene in the book, and represents the only moment of true peril or loss in the book. The rest of it is not nearly so action-packed and awesome.

Day Star was not the best science fiction book I’ve ever read. Far from it. It was almost completely lacking in characterization or, as I noted, any real loss or struggle. Even at around 125 pages, it was a slog to read at times due to the dreamlike, overwrought style of the author. Geston explained too much and showed too little, especially when it came to his character’s thoughts and feelings. However, the explanations were so labored, they obscured more than they revealed.

Yet all that said, Day Star is unlike any other work of science fiction, or even just plain fiction, that I’ve ever read.

The story involves Thel and his uncle, who is little more than a living ghost, undertaking an adventure along the Continental Highway from the depressing town of R (the civilization that founded these cities was known for administrative simplicity) to the legendary city of Ferrin. Ferrin once used a semi-mythological, semi-technological device called the Day Star to open up portals to other worlds.

The cosmology of The Day Star is that of a universe inside a nautilus’s shell, the opening of which empties into never-ending Chaos. The people of Ferrin expanded outward into ever-larger chambers of the shell, but ultimately let Chaos in (depicted as the sickly yellow storm of the cover), leading Ferrinites to retreat through the chambers of the shell. In the process, they retreated directly into the “time wind,” which caused rapid aging. Thel’s uncle was part of that retreat in the distant past, and the “time wind” eroded him away to a barely-visible outline. He’s not dead, just incomplete, as tiny particles of him are scattered all along the Continental Highway.

If this plot sounds like a New Age hippie acid trip, it kind of is. This novel is far more conceptual than it is character- or even plot-driven. I kept expecting the trip down the Continental Highway back to Ferrin, the two characters bringing along a shard of the Day Star, would be full of high-tech sorcery and wild brushes with death. Instead, it’s pretty much a leisurely stroll, the time wind at their backs, allowing Thel’s uncle to rematerialize.

All that said, I’m glad I stuck with the book. There is a streak of melancholy throughout it that points to the book’s ultimate lesson: humanity’s efforts to achieve immortality (the dream of the Ferrinites being to beat the “time wind” and eliminate death entirely) through creating perfect order in the world are doomed to failure.

Not only do our foolish experiments in AI represent our technological hubris, but the Gnostic obsession with transhumanism does as well. They are feeble, misguided, and dangerous attempts to circumvent death and achieve terrestrial mortality.

They are, fundamentally, a rejection of Christ and His Promise of Everlasting Life. There is an inherent selfishness in the transhumanist’s quest: “I don’t want the Eternal Life that Christ Gives because that requires me to give up my own desires and my Self to Him; instead, I’ll use technology to cheat death and achieve immortality on my terms.” It is the world’s oldest religion, Gnosticism: man becoming god through the accumulation of knowledge.

To be clear, I’m not opposed to the development of technology to improve and preserve human life. But the purpose here matters: using medicine or surgery to treat an illness or a condition is one thing; using it in a vain attempt to avoid death indefinitely is entirely another. That some will fail to see the distinction is perhaps a symptom of our modern age. I can’t tell you how long a human life should be—the longer the better, I’m sure!—but we can never avoid death, no matter how long we prolong it.

Ultimately, the best science fiction not only tells us about who we are, or could be; it is a warning against the follies of trying to conquer death.

Only One Man ever did that, and He Did it so that we don’t have to do so. Because Christ conquered death, we can live eternally in Him.

Wonderful review. And I love your conclusion!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Audre!

LikeLike

I find science fiction to be the MOST important literary genre.

Firstly, it spreads ideas – ideas that, once sown in the right people’s minds, lead to actual discoveries and advancements in tech, while at the same time positing the drawbacks and dangers of those discoveries and/or advancements.

Secondly, science fiction provides a remove from reality, allowing for social concepts to be questioned w/o raising too many hackles too far – e.g., Kirk and Uhura kissing… or just Uhura being a Dept. Head and bridge crew (MLK convinced her not to quit after season 1 for a reason).

We need Sci-Fi. It is literally the cradle of the future and lets people envision what might be – good, bad, or merely different – allowing others with the engineering/science/ whatever skills to perhaps bring that future about or prevent it from coming to be.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Excellent comment.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Excellent points, jonolan. Sounds like you have a blog post of your own!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Perhaps, my friend, perhaps.

LikeLiked by 2 people

What are some of your favorite science fiction books and/or short stories?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Too many to list, but here’s some general faves of mine:

Asimov’s I, Robot series and his Foundation series, anything by Heinlein, Haldeman’s Forever War trilogy, and almost anything by H. Beam Piper.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I’ve gotta check out Piper. I’m finally getting around to reading Heinlein—far too late in life! The _I, Robot_ and _Foundation_ series are also among my favorites.

LikeLiked by 1 person

A good, cheap start to Piper’s works: https://amzn.to/3Nz8InU

LikeLiked by 2 people

Excellent! I’ll pick that up shortly. Thanks, jonolan!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Also, IMHO, a needed start to- or early addtions to Heinlein reading should be the Heinlein Juveniles he wrote for Scribner. These are incredible exemplar’s of what I was talking about.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I’ll check them out. I’ve heard about his Juveniles before from other writers, and the premises for his stories always sound fascinating.

LikeLiked by 1 person