It’s SPRING BREAK, baby! Finally, at long last, yours portly has eleven glorious days (counting weekends) to recuperate from a rather brutal semester, before slogging through one more round of it.

I typically experience severe burnout about twice a year, and it has hit hard lately. I’m sleeping poorly, working constantly, and eating excessively. My overall health has suffered, and I need to shut down for a few days.

Shut down—and read short stories! Every year I offer up my Spring Break Short Story Recommendations, which will start up next week. But here is a little preview of a past story recommendation.

With that, here is 6 April 2023’s “TBT: Spring Break Short Story Recommendation 2022: ‘Witch’s Money’“:

It’s SPRING BREAK! One of my multiple cushy, extended breaks—the primary perk of dedicating one’s life to the molding of young minds—has now commenced, which means next week I’ll be inundating you with reviews of short stories, as is this blog’s Spring Break tradition.

One story I read last year was John Collier‘s “Witch’s Money.” It’s the tale of a haughty artist who succumbs to the ignorance and greed of peasants who think that checks are a magic source of money. I read it when I was quite young—to young to appreciate its nuances at the time—and it made an impression on me. Don’t write a check your butt can’t cash… or, at the very least, don’t write checks in lands where people don’t understand the basics of modern banking.

With that, here is 20 April 2022’s “Spring Break Short Story Recommendation 2022: ‘Witch’s Money’“:

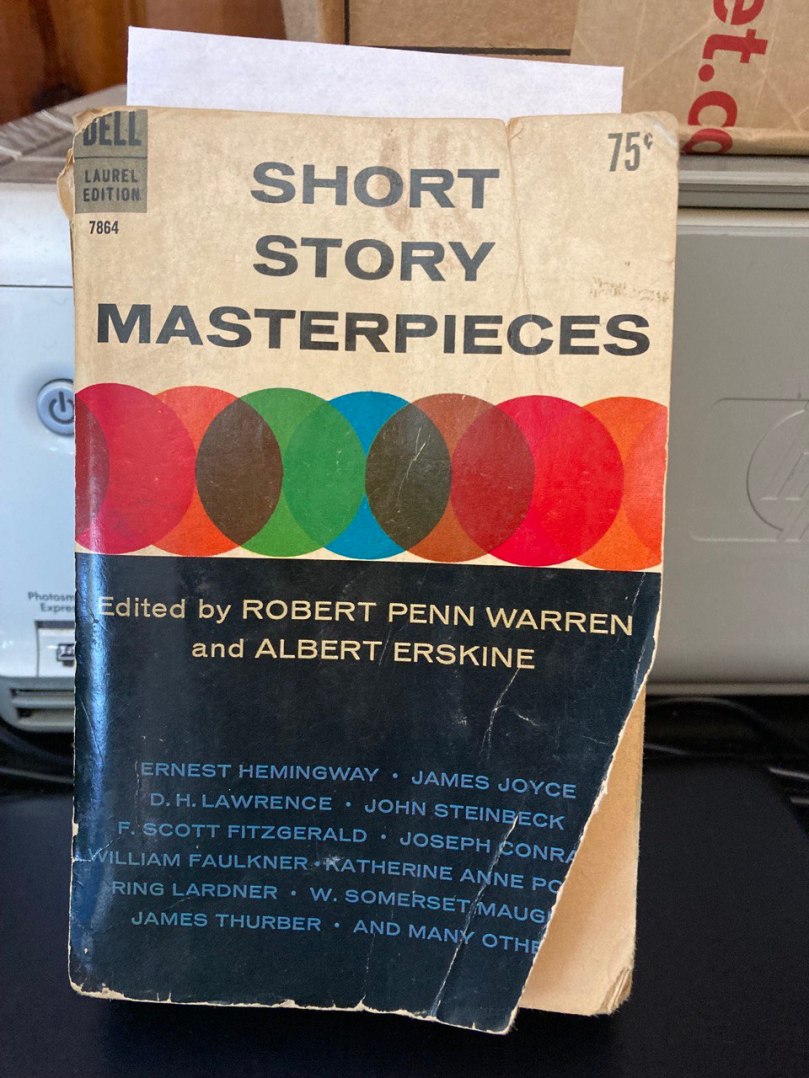

Today’s Spring Break Short Story Recommendation 2022 comes from a very old, very tattered collection of short stories I purchased probably twenty or more years ago. I think I picked it up on a trip with my grandparents when I was somewhere between the ages of ten and thirteen, the amorphous “tween” years.

The collection is called, simply, Short Story Masterpieces, and boasts Robert Penn Warren as one of its editors (the other being Albert Erskine). I have a vague recollection of attempting to read some of the stories in our hotel room the night that I bought it, and realized that these stories were way over my head at that time. I could read the words, but I could not comprehend them, at least not fully.

However, one story that always stuck out to me was John Collier‘s “Witch’s Money.” I probably flipped to that story because it had “witch” in the title, and even back then ghost stories and the like fascinated me. The story—which was published in The New Yorker in 1939—has little to do with hags and haunts, but instead explores a fatal misunderstanding about the nature of “cheques” (or “checks” to my fellow American readers).

Until I sat down to write this blog post, I couldn’t remember the outcome of this story, but I knew it involved a brash, flamboyant artist visiting the backwoods of Spain. He pays a peasant to rent a farmhouse or the like where he can work, and he writes a check to pay for it. The peasant doesn’t understand, and the artist has to explain to him how checks work.

What I vividly remember from the story is an entire exchange between the peasant and a bank clerk, who has to patiently explain to the peasant how opening an account works, and that there is a fee for cashing the check (the peasant is upset when he gets less money that is written on the face of the check).

That is about all I remembered. As a kid, I was struggling to make sense of the setting (the Pyrenees) and the fact that the peasant did not know what a check was. When I figured that out, I felt like a genius.

Apparently, everyone else in town finds out that the brash artist is handing out slips of paper worth a certain amount of money (again, they don’t understand how checking works, so they just assume that if he wrote one large check, he could write more). The townspeople decide to murder the artist and steal his checks, with every family getting two checks.

With what they believe to be large sums of money, the people go on a spending spree, building up and modernizing their town.

The story ends with the gang of peasant men heading to a larger village—after deciding to pave the mule track to the main road—and partying at cafes along the way.

It’s not the best story in the world, but it’s one that has stuck with me after all these years. I’ve always found these “fatal misunderstanding” stories entertaining, too, and they always give me pause. Greed and envy are powerful sins; coupled with ignorance, they make for a toxic brew.

good

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you.

LikeLike