This week is MAGAWeek2023, my celebration of the men, women, and ideas that MADE AMERICA GREAT! Starting Monday, 3 July 2023, this year’s MAGAWeek2023 posts will be SubscribeStar exclusives. If you want to read the full posts, subscribe to my SubscribeStar page for as little as $1 a month. You’ll also get access to exclusive content every Saturday.

America is a Christian nation. At least, it was. The Christian roots of the nation run deep, not just to the Founding (if we take “The Founding” to be in or around 1776), but far back into the colonial period. Most readers will know the well-worn story of the Pilgrims—a group of Puritan Separatists who, while not seeking religious freedom for others, at least sought it for their own peculiar version of Christianity—and their arrival in Massachusetts in 1620 (the Southerner in me will be quick to note that, despite the Yankee supremacist narrative, permanent English settlement began in 1607 with the founding of Jamestown in Virginia—the South; the earlier, albeit failed, attempt to settle Roanoke was also in the South, in what is now North Carolina, in 1585).

But there is more to the history of Christianity in America than the Puritans—much more. The colonies of British North America struggled through some fairly irreligious times (colonial Americans were much heavier drinkers than we are), and while denominations abounded—Tidewater Anglicans, Scotch-Irish Presbyterians and Catholics, New England Puritans, and Mid-Atlantic sects of various stripes—the fervor of American religiosity was at a low ebb in the late 1600s. Economic prosperity following difficult years in the 1670s—King Philip’s War in New England, Bacon’s Rebellion in Virginia—led many to move away from the church. In Puritan New England, where voting rights and citizenship required church membership (and church membership was not as easy to obtain as it is today; it required proof of one’s “election”), the Puritan-descended Congregationalist churches began offering “half-elect” membership, as there were so few citizens who could prove their “election.”

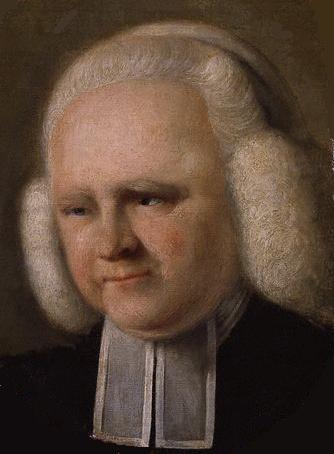

Into this void stepped the revivalists of the First Great Awakening. In the 1730s and 1740s (give or take a decade or two), a series of religious revivals swept throughout England and British North America (the colonies). These men—Charles Wesley, John Wesley, Jonathan Edwards, and George Whitefield, among others) took difficult, strenuous tours throughout England and the colonies to deliver the Gospel in a powerful, compelling way.

Their impact was immense: preaching salvation and a personal relationship with Christ, these men united the profusion of denominations and theologies in the colonies with the universal message of Christ’s Gospel. Granted, denominational and theological differences persisted—indeed, they proliferated, with John Wesley’s Methodism among the plethora of new denominations—but the grand paradox of the First Great Awakening is that, even with that denominational diversity, Americans across the colonies developed a unified identity as Christians. Protestant Christians, to be sure, and of many stripes. But that tolerance of denominational diversity, coupled with the near-uniformity of belief in Christ’s Saving Grace, forged a quintessentially American religious identity.

Most readers will be quite familiar with the Wesley Brothers, especially John, and we probably all read Jonathan Edwards’s powerful sermon “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God” in high school. But most Americans know precious little about the revivalist George Whitefield, whose prowess as a speaker and evangelist brought untold thousands to the Lord.

To read the rest of today’s MAGAWeek2023 post, head to my SubscribeStar page and subscribe for $1 a month or more!