I’m still struggling with fever and migraines, although both seem to be improving and growing milder. Fortunately, I received word today that I do not have The Virus. So now I have to get to the bottom of whatever malady plagues me.

Yesterday I launched the Summer 2020 session of History of Conservative Thought online; you can read about our discussion here. As such, it seemed a good time to look back 2019’s “What is Conservatism?,” the first post from the Summer 2019 run.

The post here details Russell Kirk’s “Introduction” to The Portable Conservative Reader, which has also been repackaged as “Ten Conservative Principles.” It’s an important essay that details the general principles and attitudes of the conservative as he attempts to make sense of the world.

It’s influential, too, though Kirk’s influence has suffered somewhat versus Buckley-style fusionism. The Z Man dedicated an entire podcast to the essay a few weeks ago.

It’s well worth a read. But for now, here’s my summary of it in “What is Conservatism?“:

Today I’m launching a summer class at my little private school here in South Carolina. The course is called History of Conservative Thought, and it’s a course idea I’ve been kicking around for awhile. Since the enrollment is very small, this first run is going to be more of an “independent study,” with a focus on analyzing and writing about some key essays and books in the conservative tradition. I’ll also be posting some updates about the course to this blog, and I’ll write some explanatory posts about the material for the students and regular readers to consult. This post will be one of those.

Course Readings:

Most of the readings will be digitized or available online at various conservative websites, but if you’re interested in following along with the course, I recommend picking up two books:

2.) The Portable Conservative Reader (edited by Russell Kirk): we’ll do some readings from this collection, including Kirk’s “Introduction” for the first week.

Course Scope:

I’ll be building out the course week-to-week, but the ultimate goal is to end with 2016 election, when we’ll talk about the break down of the postwar neoliberal consensus, the rise of populism and nationalism in the West, and the emergence of the Dissident Right.

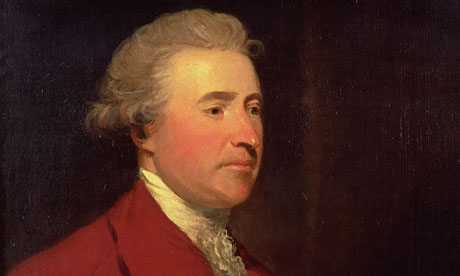

After the introductory week, we’ll dive into Edmund Burke, then consider the antebellum debates about States’ rights. I haven’t quite worked out the murky bit during the Gilded Age, but we’ll look at the rise of Progressivism in the early twentieth century, then through the conservative decline during the Great Depression and the Second World War.

After that, it’s on to Buckley conservatism and fusionism, as well as the challenges of the Cold War and international communism. Paleoconservatives like Pat Buchanan and (if I’m feeling edgy) Sam Francis will get shout-outs as well.

Week 1: What is Conservatism?

That’s the basic outline. For the first day, we’re going to look at the question in the title: what is conservatism? What makes one a conservative? Feel free to comment below on your thoughts.

After we see what students think conservatism is, we’ll begin reading through Russell Kirk’s “Introduction” in The Portable Conservative Reader. It’s an excellent overview of the question posed. The first section of the lengthy “Introduction” is entitled “Succinct Description,” and it starts with the question, “What is conservatism?”

Not being one to reinvent what others have done better—surely that is part of being a conservative (see Principle #3 below)—I wanted to unpack his six major points. Kirk argues that though conservatism “is no ideology,” and that it varies depending on time and country, it

“may be apprehended reasonably well by attention to what leading writers and politicians, generally called conservative, have said and done…. to put the matter another way, [conservatism] amounts to the consensus of the leading conservative thinkers and actors over the past two centuries.”

Kirk condenses that grand tradition into six “first principles,” derived largely from British and American conservatives. To wit:

1.) Belief in a Transcendent Moral Order – conservatives believe there is higher authority or metaphysical order that human societies should build upon. As Kirk puts it, a “divine tactic, however dimly descried, is at work in human society.” There is a need for “enduring moral authority.” The Declaration of Independence, for example, draws on the concept of “natural law” to complain about abuses of God-given rights. The implication is that a good and just society will respect God’s natural law.

2.) The Principle of Social Continuity – Kirk puts this best: “Order and justice and freedom,” conservatives believe, “are the artificial products of a long and painful social experience, the results of centuries of trial and reflection and sacrifice.”

As such, the way things are is the product of long, hard-won experience, and changes to that social order should be gradual, lest those changes unleash even greater evils than the ones currently present. Conservatives abhor sudden upheaval; to quote Kirk again: “Revolution slices through the arteries of a culture, a cure that kills.”

3.) The Principle of Prescription, or the “wisdom of our ancestors” – building on the previous principle, “prescription” is the belief that there is established wisdom from our ancestors, and that the antiquity of an idea is a merit, not a detraction. Old, tried-and-trued methods are, generally, preferable to newfangled conceptions of how humans should organize themselves.

As Kirk writes, “Conservatives argue that we are unlikely, we moderns, to make any brave new discoveries in morals or politics or taste. It is perilous to weigh every passing issue on the basis of private judgment and private rationality.” In other words, there is great wisdom in traditions, and as individuals it is difficult, in our limited, personal experience, to comprehend the whole.

It’s like G. K. Chesterton’s fence: you don’t pull down the fence until you know why it is built. What might seem to be an inconvenience, a structure no longer useful, may very well serve some vital purpose that you only dimly understand, if at all.

4.) The Principle of Prudence – in line with Principles #2 and #3, the conservative believes that politicians or leaders should pursue any reforms only after great consideration and debate, and not out of “temporary advantage or popularity.” Long-term consequences should be carefully considered, and rash, dramatic changes are likely to be more disruptive than the present ill facing a society. As Kirk writes, “The march of providence is slow; it is the devil who always hurries.”

5.) The Principle of Variety – the “variety” that Kirk discusses here is not the uncritical mantra of “Diversity is Our Strength.” Instead, it is the conservative’s love for intricate variety within his own social institutions and order.

Rather than accepting the “narrowing uniformity and deadening egalitarianism of radical systems,” conservatives recognize that some stratification in a society is inevitable. Material and social inequality will always exist—indeed, they must exist—but in a healthy, ordered society, each of these divisions serves its purpose and has meaning. The simple craftsman in his workshop, while materially less well-off than the local merchant, enjoys a fulfilling place in an ordered society, one that is honorable and satisfying. Both the merchant and the craftsmen enjoy the fruits of their labor, as private property is essential to maintaining this order: “without private property, liberty is reduced and culture is impoverished,” per Kirk.

This principle is one of the more difficult to wrap our minds around, as the “variety” here is quite different than what elites in our present age desire. Essentially, it is a rejection of total social and material equality, and a celebration of the nuances—the nooks and crannies—of a healthy social order. “Society,” Kirk argues, “longs for honest and able leadership; and if natural and institutional differences among people are destroyed, presently some tyrant or host of squalid oligarchs will create new forms of inequality.”

Put another way: make everyone equal, and you’ll soon end up with another, likely worse, form of inequality.

6.) The Principle of the Imperfectibility of Human Nature – unlike progressives, who believe that “human nature” is mutable—if we just get the formula right, everyone will be perfect!—conservatives (wisely) reject this notion. Hard experience demonstrates that human nature “suffers irremediably from certain faults…. Man being imperfect, no perfect social order ever can be created.” An Utopian society, assuming such a thing were possible, would quickly devolve into rebellion, or “expire of boredom,” because human nature is inherently restless and rebellious.

Instead, conservatives believe that the best one can hope for is “a tolerably ordered, just and free society, in which some evils, maladjustments, and suffering continue to lurk.” Prudent trimming of the organic oak tree of society can make gradual improvements, but the tree will never achieve Platonic perfection (to quote Guns ‘n’ Roses: “Nothing lasts forever, even cold November rain”).

Conclusion

Kirk stresses in the rest of the introduction that not all conservatives accept or conform to all of the six principles again; indeed, most conservatives aren’t even aware of these principles, or may only dimly perceive them.

That’s instructive: a large part of what makes one conservative is lived experience. “Conservatism” also varies depending on time and place: the social order that, say, Hungary seeks to preserve is, of necessity, different than that of the United States.

Conservatism, too, is often a reaction to encroaching radicalism. Thus, Kirk writes of the “shop-and-till” conservatism of Britain and France in the nineteenth century: small farmers and shopkeepers who feared the loss of their property to abstract rationalist philosophers and coffeeshop radicals, dreaming up airy political systems in their heads, and utterly detached from reality.

If that sounds like the “Silent Majority” of President Richard Nixon’s 1968 and 1972 elections—or of President Trump’s 2016 victory—it’s no coincidence. The great mass of the voting public is, debatably, quietly, unconsciously conservative, at least when it comes to their own family, land, and local institutions. Those slumbering hordes only awaken, though, when they perceive their little platoon is under siege from greater forces. When they speak, they roar.

But that’s a topic for another time. What do you think conservatism is? Leave your comments below.

–TPP