The Summer 2020 session of History of Conservative Thought is really going well. Yesterday, the three young man each gave brief presentations on three excerpts from Edmund Burke’s writing, summarizing Burke’s main points and ideas.

It was made for a lively, far-ranging discussion. One of the students is taking another summer course, Terror and Terrorism, a popular summertime offering from one of my colleagues. I had the pleasure to fill-in last summer for the French Revolution portion of that class while my colleague was away at an AP Summer Institute. Apparently, that course just covered the French Revolution again, so it dovetailed nicely with our discussion of Burke’s Reflections on that bloody affair. We had a good time contrasting Burkean “ordered liberty” and Rousseau’s “general will.”

As such, I thought this edition of TBT could look back to Summer 2019’s HoCT update, “History of Conservative Thought Update: Edmund Burke“:

A bit of a delayed post today, due to a busier-than-usual Monday, and the attendant exhaustion that came with it. The third meeting of my new History of Conservative Thought class just wrapped up, and while I should be painting right now, I wanted to give a quite update.

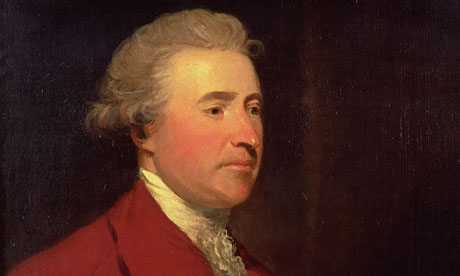

Last week, we began diving into the grandfather of modern conservatism, Edmund Burke. Burke prophetically saw the outcome of the French Revolution before it turned sour, writing his legendary Reflections on the Revolution in France in 1789 as the upheaval began. Burke argued that the French Revolution ended the greatness of European civilization, a Europe that governed, in various ways, its respective realms with a light hand, and a sense of “moral imagination.”

To quote Burke reflecting on the Queen of France:

“I thought ten thousand swords must have leaped from their scabbards to avenge even a look that threatened her with insult. But the age of chivalry is gone. That of sophisters, economists, and calculators, has succeeded; and the glory of Europe is extinguished forever. Never, never more, shall we behold that generous loyalty to rank and sex, that proud submission, that dignified obedience, that subordination of the heart, which kept alive, even in servitude itself, the spirit of an exalted freedom. The unbought grace of life, the cheap defence of nations, the nurse of manly sentiment and heroick enterprise is gone! It is gone, that sensibility of principle, that chastity of honour, which felt a stain like a wound, which inspired courage whilst it mitigated ferocity, which ennobled whatever it touched, and under which vice itself lost half its evil, by losing all its grossness.”

What a powerful excerpt! The “sophisters, economists, and calculators,” indeed, reign in the West. What Burke was driving at here was that the rationalistic, abstract bureaucrats who would abandon tradition in their quest for a perfect society would sacrifice everything that made their country great, and life worth living.

Burke was also arguing that there is more to obedience to a government or king than the mere threat of power. People are invested in their country and society—and willing to submit to authority—because of organic culture from which it grows. Uprooting the great tree of tradition in favor of abstract foundations merely destroys the tree, and plants its seedlings in shallow ruts of stone. What grows will be anemic and pitiful by comparison.

Volumes could and have been written about Burke, but I’ll leave it here for now. Next week we’re getting into the development of Northern and Southern conservatism, which should make for some pre-Independence Day fun.