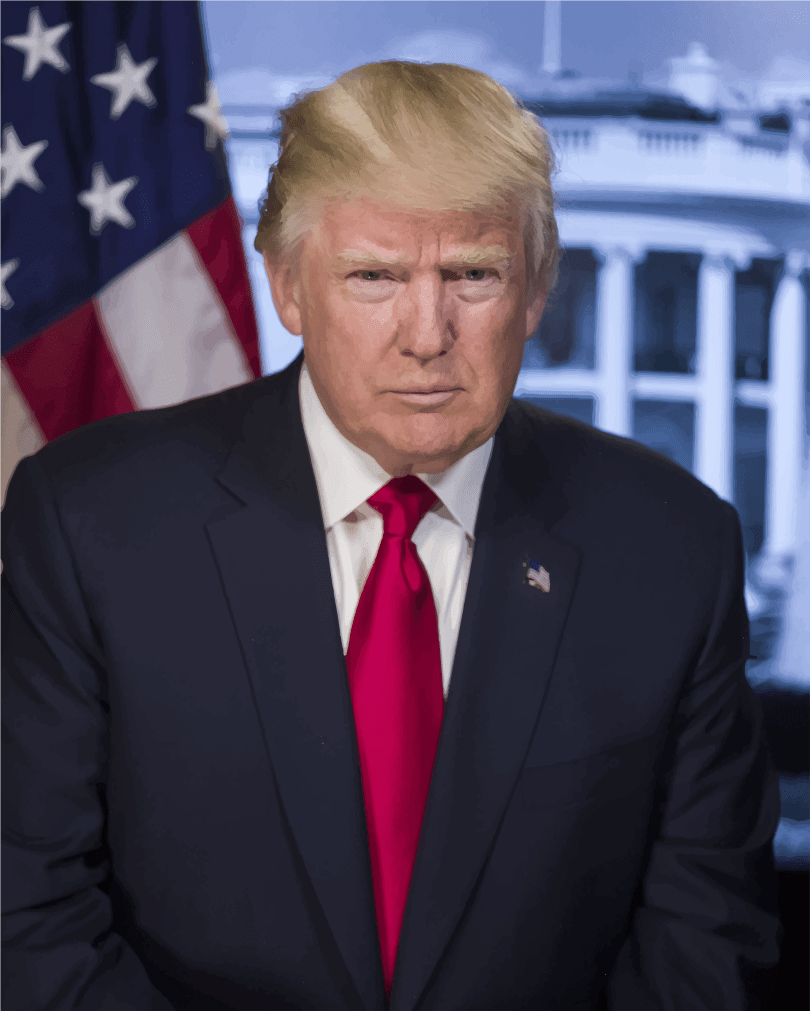

Because I was out sick from work yesterday (and will be again today), I needed a way to cover Secretary of State and President John Quincy Adams with one AP United States History class that was slightly behind the others (in part to our strange, rotating schedule). It occurred to me that I had written nearly 2000 words on the great Secretary of State back in 2018, during the first ever #MAGAWeek. Why not have the students read that?

So, given my decrepit—but improving!—situation, I thought I’d dedicate today’s TBT to the man who was, perhaps, the greatest Secretary of State in American history—the oft-forgotten, much-maligned John Quincy Adams:

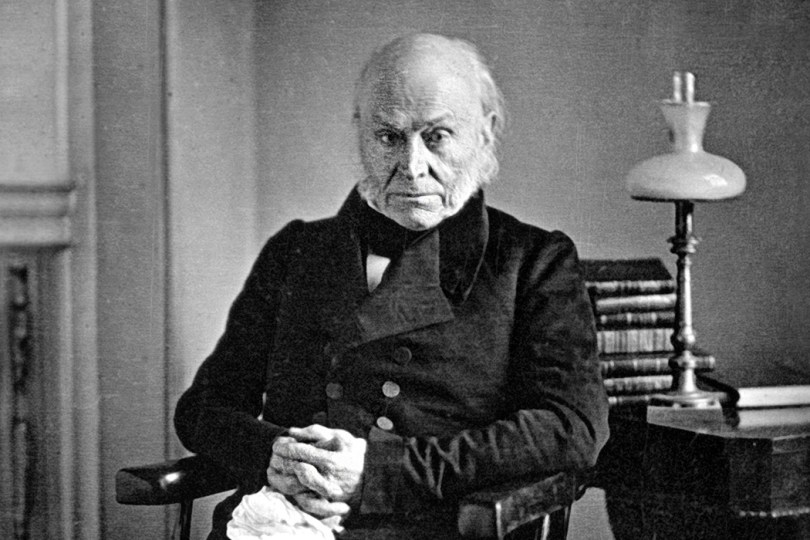

John Quincy Adams

If yesterday’s MAGA Week profile of George Washington was straight from “American History Greatest Hits, Volume I,” today’s selection is like a bootlegged deep-cut from an obscure local musician’s live show. John Quincy Adams—an American diplomat, Secretary of State, President, and Congressman—deserves better.

US History students of mine for years have recoiled at the dour daguerreotype portrait of our somewhat severe sixth President. But behind that stern, austere visage churned the mind of a brilliant, ambitious man—and probably the greatest Secretary of State in American history. I will be focusing on Adams’s tenure in that position in today’s profile.

An “Era of Good Feeling”

Adams was one of several “all-star” statesmen of the second generation of great Americans. After the careers of George Washington, Alexander Hamilton, Thomas Jefferson, and John Quincy’s father, John Adams, a new, youthful cadre of ambitious and talented national leaders took their place at the helm of a nation that was growing and expanding rapidly. From the ill-fated War of 1812 through the Mexican War, leaders like John C. Calhoun, Daniel Webster, Henry Clay, and Andrew Jackson—the populist odd-man out—forged a national identity and sought to navigate the nation through its early growing pains.

John Quincy Adams was among this group. After the War of 1812, his father’s old Federalist Party largely died out, both due to the treasonous actions of the so-called “Blue Light” Federalists (who openly sided with the British) and to demographic changes brought about by westward expansion and the Louisiana Purchase in 1803. More Americans were small, yeoman farmers, and the Federalists’ pro-British, pro-industry, pro-commerce platform held little appeal for feisty frontiersman who were suspicious of a strong federal government and the hated Second Bank of the United States, charted in 1816.

As such, the United States entered an “Era of Good Feeling” under President James Monroe, in which one party, the Democratic-Republican Party, remained. Monroe’s cabinet was a “who’s who” of young, dynamic men, and Adams was his Secretary of State.

Secretary of State

It was in this context that Adams made his most significant contributions to American foreign policy and nationalism. While serving as Secretary of State, he laid out a vision for America’s future that held throughout the nineteenth century.

In essence, Adams argued that the United States should pursue a realist foreign policy that avoided wars and foreign entanglements; that the nation should not seek a European-style “balance of power” with its Latin American neighbors, but should be exercise hegemonic dominance in the Western Hemisphere; and that the United States should gain such territory as it could diplomatically.

In 1821, Adams famously issued his warning against involvement in foreign wars of liberation. The context for this warning was the Greek War of Independence from the Ottoman Empire, an endeavor that was hugely popular in Europe, particularly in Britain. Many Americans urged Congress to intervene in the interest of liberty, and for Americans to at least send arms to help in another fledgling nation’s war for independence.

Adams perceptively saw the dangers inherent in the United States involving itself in other nations’ wars, even on the most idealistic of grounds. To quote Adams at length:

“Wherever the standard of freedom and Independence has been or shall be unfurled, there will her heart, her benedictions and her prayers be. But she goes not abroad, in search of monsters to destroy. She is the well-wisher to the freedom and independence of all. She is the champion and vindicator only of her own. She will commend the general cause by the countenance of her voice, and the benignant sympathy of her example. She well knows that by once enlisting under other banners than her own, were they even the banners of foreign independence, she would involve herself beyond the power of extrication, in all the wars of interest and intrigue, of individual avarice, envy, and ambition, which assume the colors and usurp the standard of freedom. The fundamental maxims of her policy would insensibly change from liberty to force…. She might become the dictatress of the world. She would be no longer the ruler of her own spirit.” (Emphasis added; Source: https://www.mtholyoke.edu/acad/intrel/jqadams.htm)

If America were to involve itself in open-ended wars of liberation—even once!—it would set a dangerous precedent that the United States would become constantly embroiled in the squabbles of other nations. No matter how well-meaning, such intervention would commit the nation to a disastrously unlimited policy of nation-building and war.

The Transcontinental Treaty (1819)

Prior to rumblings for intervention in Greece, Adams brokered the purchase of Spanish Florida in a rather amusing fashion. The hero of the Battle of New Orleans, General Andrew Jackson, pursued a group of Seminole Indians into Florida, violating orders to respect the international border. In the process, Jackson attacked a fort manned by Seminoles and escaped slaves, killed two British spies, and burned a Spanish settlement.

Instantly, an international crisis seemed imminent. To a man, President Monroe’s cabinet demanded disciplinary action be taken against General Jackson. It was Adams—who, ironically, would become Jackson’s bitterest political opponent in 1824 and 1828—argued against any such action, and planned to use Jackson’s boldness to America’s advantage.

With apologies to Britain and Spain, Adams pointed out that, despite the government’s best efforts, Jackson was almost impossible to control, and was apt to invade the peninsula again. Further, Spanish rule in Florida was increasingly tenuous, due to the various Latin American wars of independence flaring up at the time. With revolts likely—and facing the prospect of another Jackson invasion—Spain relented, selling the entire territory for a song.

The Oregon Country and the Convention of 1818

Adams was also key in securing the Oregon Country for the United States, although the process was not completed in full until James K. Polk’s presidency, some thirty years later. The Oregon Country—consisting of the modern States of Washington and Oregon—was prime land for settlement, but the United States and Great Britain both held valid claims to the territory.

Adams realized that the United States could afford to be patient—given America’s massive population growth at the time, and its citizens’ lust for new lands, Adams reasoned that, given enough time, American settlers would quickly outnumber British settlers in the territory.

Sure enough, Adams secured another territory for the United States, albeit in far less dramatic fashion that the acquisition of Florida one year later.

The Monroe Doctrine (1823)

Perhaps Adams’s greatest contribution to the United States was his work on the Monroe Doctrine in 1823. Once again, Adams’s diplomatic brilliance came into play.

Adams sought to keep the United States out of foreign wars, but he also wanted to keep European powers out of the Western Hemisphere. As Spain continued to lose its grip on its American colonies, the autocratic nations of Russia, Prussia, and Austria (the Austrian Hapsburg controlled Spain at this time) sought to reestablish monarchical rule in the Western Hemisphere.

President Monroe and Secretary Adams were having none of it—nor was was Great Britain, which enjoyed a brisk trade with the newly-independent republics of Latin America. To that end, Britain proposed issuing a joint statement to the world, with the effect of committing both nations to keeping the new nations of Latin American independent.

Monroe was excited at the idea, but in his ever-prescient manner, Adams argued for caution. Were the United States to issue the declaration jointly with Britain, they would appear “as a cockboat in the wake of a British man-o-war.” It would be better, Adams argued, to issue a statement unilaterally.

The United States had no way, in 1823, to enforce the terms of the resulting Monroe Doctrine, which pushed for three points: Europe was to cease intervention in the affairs of the Western Hemisphere (non-intervention); Europe was to cease acquiring new colonies in the Western Hemisphere (non-colonization); and the United States would stay out of open-ended entanglements and alliances with Europe (isolation).

However, Adams knew that Britain would enforce the Monroe Doctrine with its mighty navy, even if the United States issued it unilaterally, because it would be in Britain’s national interest to do so. Sure enough, Adams’s shrewd realism won the day, and, other than France’s brief occupation of Mexico during the American Civil War, European powers never again established colonies in the New World.

After Monroe’s Cabinet

For purposes of space and length, I will forego a lengthy discussion of Adams’s presidency and his tenure in Congress. He was an ardent nationalist in the sense that he sought an ambitious project of internal improvements—roads, canals, harbors, and lighthouses—to tie the young nation together. In his Inaugural Address, he called for investment in a national university and a series of observatories, which he called “lighthouses of the sky,” an uncharacteristically dreamy appellation that brought him ire from an already-hostile Congress.

His presidency, too, was marred by the unusual circumstances of his election; Adams is the only president to never win the popular or electoral vote, or to ascend to the position from the vice presidency. That’s a story worth telling in brief, particularly for political nerds.

The presidential election field of 1824 was a crowded one, and the “Era of Good Feeling” and its one-party dominance were showing signs of sectional tension (indeed, the second system of two parties, the National Republicans—or “Whigs”—and Jackson’s Democratic Party, would evolve by 1828). There were four candidates for president that year: Andrew Jackson, John Quincy Adams, Speaker of the House Henry Clay, and Secretary of Treasury William Crawford of Georgia.

Jackson won a plurality of the electoral votes—99—but no candidate had a clear majority. In this event, the top three candidates are thrown to the House of Representatives, where each State’s delegation votes as one. Crawford, who finished third, was deathly ill, and was not a suitable candidate, and Henry Clay, in fourth, was not eligible constitutionally.

That left the rabble-rousing Jackson and the austere Adams. Clay, as Speaker of the House, held immense influence in Congress, and could not stand Jackson, so he threw his support behind Adams, who won the election in Congress.

Apparently losing all the wisdom and prudence of his days at the State Department, Adams foolishly named Clay as his new Secretary of State—an office that, in those days, was perceived as a stepping stone to the presidency. Jackson supporters immediately cried foul, arguing that it was a “corrupt bargain” in which Clay sold the presidency in exchange for the Cabinet position.

While it appears that Adams sincerely believed Clay was simply the best man for the job, the decision cast a pall over his presidency, and Jackson supporters would gleefully send their man to the Executive Mansion in 1828.

At that point, Adams expected to settle into a quiet retirement, but was elected to represent his congressional district in 1830. During his time in Congress, he fought against slavery and the infamous “gag rule,” which prevented Congressman from receiving letters from constituents that contained anti-slavery materials. He was also a vocal opponent of the Mexican War—as was a young Abraham Lincoln during his single term in Congress—and died, somewhat disgracefully, while rising to oppose a measure to honor the veterans of that war.

Regardless, Adams’s career shaped the future of the country, gaining it international prestige and setting it on track to emerge as a mighty nation, stretching from sea to shining sea. Through his service and genius, Adams made America great—and, physically, in a very literal sense.

Quick References

- I relied heavily on my own memory and past readings for this post, thus the lack of more links in the body of this post. As such, I relied on only a few sources to refresh my memory.

- Library of Congress: https://www.loc.gov/rr/program/bib/presidents/jqadams/memory.html

- Mount Holyoke website: https://www.mtholyoke.edu/acad/intrel/jqadams.htm

- White House website: https://www.whitehouse.gov/about-the-white-house/presidents/john-quincy-adams/

- World History Project: https://worldhistoryproject.org/1823/10/17/president-james-monroe-writes-a-letter-to-thomas-jefferson