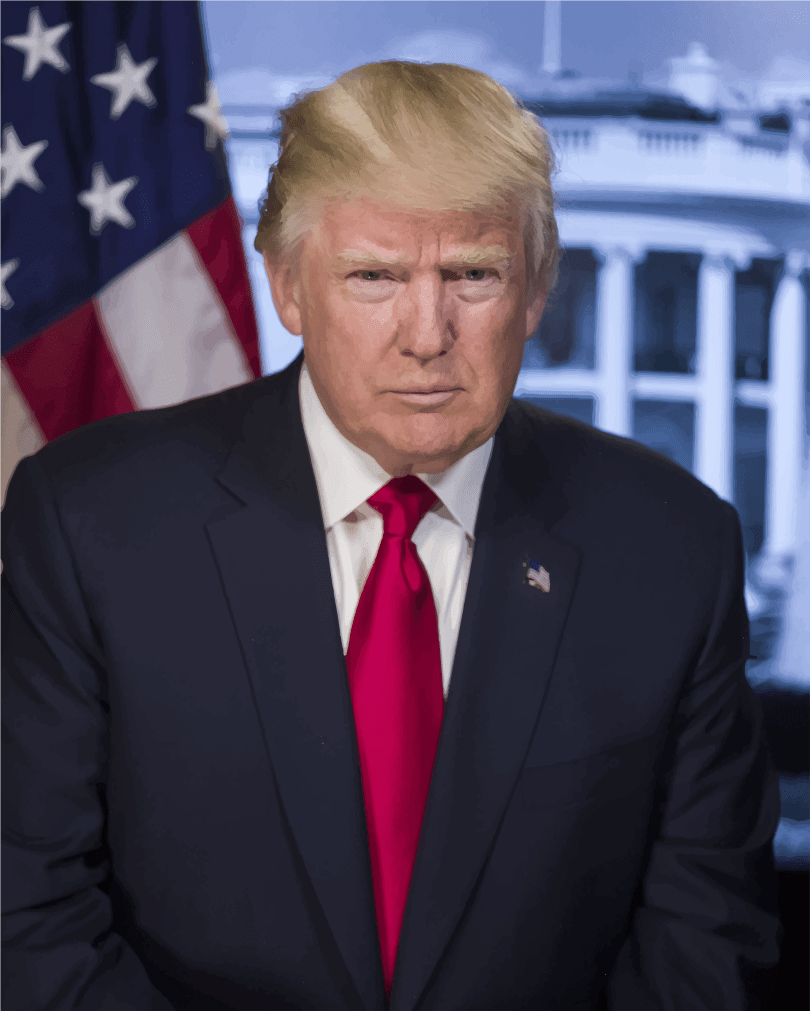

President Trump officially kicked off his 2020 reelection campaign earlier this week, and it’s been almost exactly one year since the post below. I’ve been quite impressed with President Trump, who has governed far more conservatively than I and many other conservatives could have ever hoped. While there is still much to be done on immigration—border crossings have accelerated due to misguided progressive policies that encourage child trafficking—and the wall seems to be more an abstraction than a concrete reality, Trump has slashed taxes, created jobs, and strengthened national security.

Trump has also stacked the federal courts with conservative-leaning judges and justices. And that’s in the face of progressive aggression and Deep State coup attempts.

His record speaks for itself. President Trump has taken the reins of the Republican Party and has done much to shore up the Republic. Here’s looking to four more years—and to Keeping America Great!

Father’s Day—16 June 2018—marked three years since President Donald Trump’s now-legendary descent down the golden escalator at Trump Tower, following by his controversial but true-to-form announcement that he would be seeking the Republican Party’s nomination for President.

I was, initially, a Trump skeptic, and I voted for Texas Senator Ted Cruz in the South Carolina primaries the following February. When Trump first announced, I wrote him off—as so many others—as a joke. I appreciated his boldness on immigration, but I still thought the PC Police and the campus Social Justice Warriors were firmly in control of the culture, and that no one could speak hard truths.

I also remembered his brief flirtation with running in 2012, and thought this was just another episode in what I learned was a long history of Trump considering a presidential bid. At the South Carolina Republican Party’s state convention earlier in 2015, I asked two young men working on Trump’s pre-campaign (this was before The Announcement) if he was reallyserious this time. The two of them—they looked like the well-coifed dreamboat vampires from the Twilight franchise—both assured me that Trump was for real, and I left with some Trump stickers more skeptical than ever (note, too, that this was before the distinctive but simple red, white, and blue “Trump” lawn signs, and definitely before the ubiquitous “Make America Great Again” hats).

I even briefly—briefly!—considered not voting for Trump, thinking that he was not a “real” conservative. I still don’t think he’s a conservative in the way, say, that a National Review columnist is (although, the way they’ve gotten so noodle-wristed lately, that’s a good thing; I’ve just about lost all respect for David French’s hand-wringing, and Kevin Williamson went off the deep-end), but rather—as Newt Gingrich would put it—an “anti-Leftist.” That’s more than enough for me.

But my conversion to Trump came only belatedly. I can still find a notebook of notes from church sermons in which I wrote, “Ted Cruz won the Wyoming primary. Thank God!” in the margins.

Then something happened—something I predicted would happen on the old TPP site—and I couldn’t get enough of the guy. It wasn’t a “road to Damascus” epiphany. I started listening to his speeches. I read up on his brilliant immigration plan (why haven’t we taxed remittances yet?). I stopped taking him literally, and began taking him seriously.

And I noticed it happening in others all around me. Friends who had once disdained the Republican Party were coming around on Trump. Sure, it helped that Secretary Hillary Clinton was a sleazebag suffused with the filth of grasping careerism and political chicanery. But more than being a vote against Hillary, my vote—and the vote of millions of other Americans—became a vote for Trump—and for reform.

Trump made politics interesting again, too, not just because he said outrageous stuff on live television (I attended his rally in Florence, South Carolina before the SC primaries, and I could feel his charisma from 200 feet away; it was like attending a rock concert). Rather, Trump busted wide open the political orthodoxy that dominated both political parties at the expense of the American people.

Take trade, for example. Since World War II, both Democrats and Republicans have unquestioningly supported free trade. Along comes Trump, and suddenly we’re having serious debates again about whether or not some tariffs might be beneficial—that maybe it’s worth paying a little more for a stove or plastic knick-knacks if it means employing more Americans.

That’s not even to mention Trump’s legacy on immigration—probably the most pressing issue of our time, and one about which I will write at greater length another time.

Regardless, after over 500 days in office, the record speaks for itself: lower taxes, fewer regulations, greater economic growth, greater security abroad. At this point, the only reasons I can see why anyone would hate Trump are either a.) he’s disrupting their sweet government job and/or bennies; b.) they don’t like his rhetorical style, and can’t get past it (the Jonah Goldbergite “Never Trumpers”—a dying breed—fall into this group); or c.) they’re radical Cultural Marxists who recognize a natural foe. Folks in “Option B” are probably the most common, but they’re too focused on rhetoric and “decorum”—who cares if he’s mean to Justin Trudeau if he gets results? The folks in “Option C” are willfully ignorant, evil, or blinded by indoctrination.

As the IG report from last Thursday revealed—even if it wouldn’t come out and say it—the Deep State is very, very real. That there were elements within the FBI willing to use extralegal means to disrupt the Trump campaign—and, one has to believe, to destroy the Trump presidency—suggests that our delicate system of checks and balances has been undermined by an out-of-control, unelected federal bureaucracy. Such a dangerous threat to our republic is why we elected Trump.

President Trump, keep draining the swamp. We’re with you 100%.