Back in December, I wrote a post on the old blog begging Republicans to pass tax cuts. When they did, I danced around my house like a silver-backed gorilla on Christmas.

I cannot understand objections to the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, other than fiscal conservatives’ fear of increasing deficit spending. By that I mean I can intellectually understand objections in an abstract, academic sense, but I’m unable to accept those arguments as valid in this case, and many of them are specious.

The historical record is clear: tax cuts works. Be it cuts on income, corporate, estate, or sales taxes, cutting taxes, in general, stimulates economic growth and usually increases government revenues.

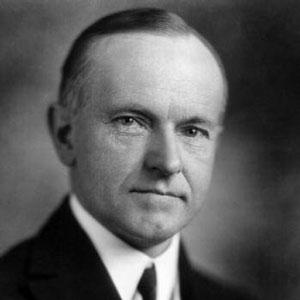

Take the example of Calvin Coolidge, whom we might call the godfather of modern tax cuts. As president, Coolidge used his predecessor’s Budget and Accounting Act of 1921 to carefully monitor and eliminate excess government spending. He also signed into law the Revenue Act of 1926, reducing the top rate to 25% on incomes greater than $100,000.

By the time he left office, the government had increased revenues (due to the stimulative effect of the tax cuts on the economy—rates fell, but more people were paying greater wages into the system), federal spending had fallen, and the size and scope of the federal government had shrunk, a feat no other president has managed to accomplish.

The perennial wag will protest, “But what about the Depression?” Certainly, there were a number of complicated reasons that fed into the coming Depression, but the stock market crash—really, a massive correction—did not cause the Depression. Had the government left well enough alone, the economy should have adjusted fairly quickly, although modern SEC rules and regulations were not in place. That’s a discussion for another post, but I suspect that Herbert Hoover’s signing of the Smoot-Hawley Tariff (1930)—a tax increase on imports—did much to exacerbate the economic situation, and a decade of FDR’s social welfare experiments injected further uncertainty into markets.

But I digress. Subsequent presidents have championed tax cuts in the Coolidge vein, albeit without the corresponding emphasis on spending cuts. John F. Kennedy pushed for tax cuts, which threw gasoline onto the fire of the post-war American economy. Ronald “Ronaldus Magnus” Reagan’s tax cuts created so much prosperity, the ’80s are remembered for hair metal and cocaine; had he not had to spend the Soviets out of existence (and faced a Democratic Congress), he could have cut spending, too.

President Trump’s tax cuts have breathed new life into a sluggish, post-Great Recession recovery. Jobs growth is increasing month after month, and wages are rising, slowly but surely. Black unemployment is down from 7.7% in January to 5.9% as of May—the first time it’s ever been below 7% since the government began keeping statistics in 1972.

Leftists object that the cut to the corporate tax rate benefits big fat cats instead of everyday Americans, but the statistics suggest otherwise (see the article linked in the previous paragraph for more good news). Further, Leftists moan and groan when companies put increased revenues into dividend payments to stockholders, as if this move is detrimental. On the contrary, as more Americans invest in mutual funds in their 401(k)s or IRAs, they stand only to gain from these investments. Progressives only see these investments as “big company benefits,” without following through on what that money does.

Of course, that’s because the Left’s focus is emotional (not economic), and worries about all the sweet government gigs that majors in Interpretative Queer Baltic Dance Studies will lose without the federal government’s largesse. Getting voters off the welfare rolls further inhibits the Democratic Party’s mantra of “Soak the Rich,” as upwardly-mobile workers naturally want to keep a good thing going.

Conservative concerns of deficit spending are more grounded in economic reality, and while the federal deficit seems like an abstraction to most Americans, it does present a looming crisis. Perpetual indebtedness in a personal sense seems inherently immoral if undertaken as a financial strategy unto itself (taking out a loan for a car, a house, a business, or education is one thing; living off of borrowed money, and borrowing more, with no intention of paying it back is quite another; I’m referencing the latter situation); the government should be held to the same standard.

That said, the problem of the federal deficit is a longstanding issue that has more to do with excessive and wasteful spending. The stimulative effect of the tax cuts, by putting more people to work, will increase revenues. The most pressing concern now is for Congress to make the income tax cuts permanent—another no-brainer, win-win move for all concerned.

Taxes are a necessary evil—we need the military, roads, and the like—and there comes a point of diminishing returns with cuts just as there are with increases, but allowing Americans to keep more of their money is, in almost every situation, the better choice, both economically and morally.