It’s going to be a very quick post today. While I’m enjoying an unexpectedly lengthy Winter Break—a perk of being a teacher, and why our complaints, while legitimate, should be taken with a grain of salt—I’m also quite busy outside of the mildly Dissident Right/”Alt-Lite” blogosphere. I played a very fun solo gig last night at a coffee shop in my neck of South Carolina, and tonight I’ll be playing alto saxophone with an old-school, swingin’ big band. I’m heading out for soundcheck and rehearsals for that soon, thus the quick post (gotta keep the streak alive!).

American Thinker posted a piece this week on the utility of border walls—how they’re popping internationally, and how they’re incredibly effective: https://www.americanthinker.com/blog/2019/02/a_fenceless_border_is_defenseless.html

Some international examples from the piece (emphasis added):

According to a February 2018 American Renaissance article, between 1945 and 1961, over 3.5 million East Germans walked across the unguarded border. When the wall was built, it cut defections by more than 90 percent. When Israel in January 2017 completed improvements to the fence on its border with Egypt to keep out terrorists and African immigrants, it cut illegal immigration to zero. In 2015, The Telegraph reported on the construction of a 600-mile “great wall” border by Saudi Arabia with Iraq to stop Islamic State militants from entering the country. The wall included five layers of fencing with watchtowers, night-vision cameras, and radar cameras. Finally, a September 2016 article in the Washington Post reported on the new construction of a mile-long wall at Calais.

In case you missed it, the key line there is “[w]hen Israel… completed improvements to the fence on its border with Egypt… it cut illegal immigration to zero.”

Cut it to zero. No one can plausibly argue against the effectiveness of a border wall. Yes, ports of entry are a problem, too, but those are merely the documented cases of illegal entry. The reason those numbers are so prominent in the debate (besides being a useful cudgel against the commonsense of a border wall) is because we have numbers—at least, more accurate numbers—for illegal entries at ports of entry as opposed to illegal entries at the porous southern border.

Again, that’s just commonsense, but it’s easy to lose in the debate. It’s hard to fight data with data when you don’t have an accurate count—and an accurate count of illegal border crossings is, by definition, impossible!

What we do know is that illegal crossings are up—why else would there be hordes of coyote-led migrants marching en masse to the border—and a wall is a quick, cost-effective way to relieve border agents to focus on other areas.

Those hordes—as much as we can and should sympathize with their plight—represent a direct assault on our borders and national sovereignty. If we let some come through illegally, simply because they come in large numbers, then the floodgates open.

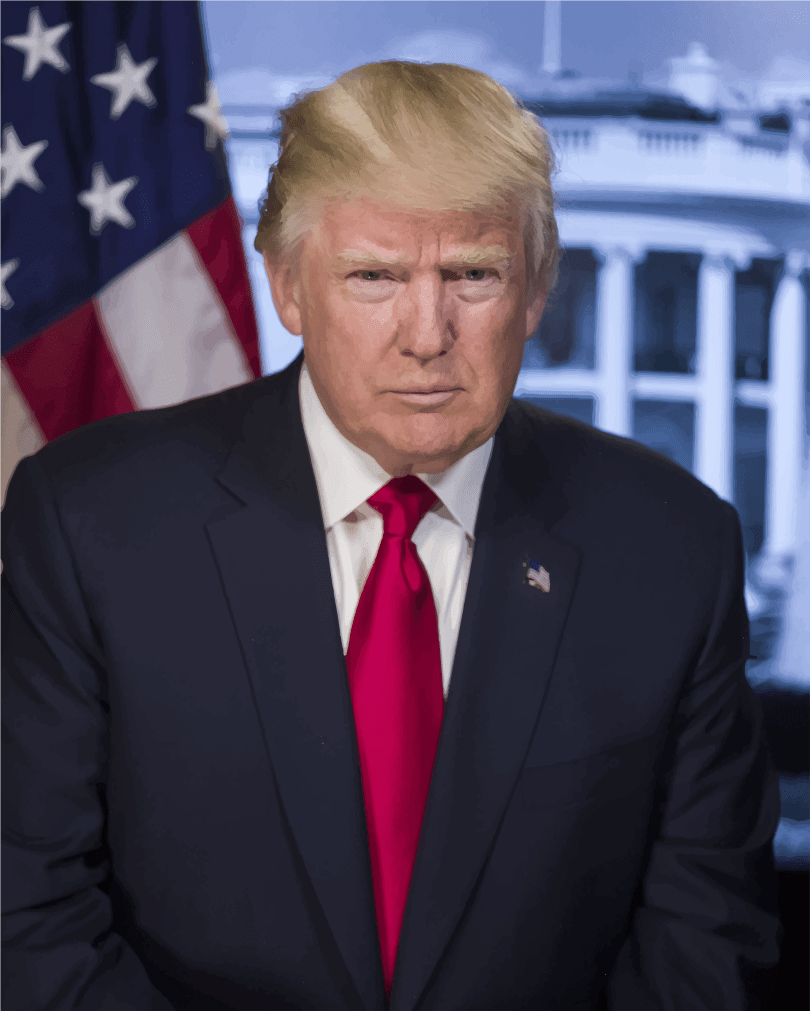

In that context—that of a foreign invasion—the President’s decision to declare a national emergency seems to be entirely in keeping with his powers under Article II of the Constitution.

While I think he should have gotten Congress to act sooner when Republicans controlled both chambers of Congress (although, let’s be honest here: many congressional Republicans are doing the bidding of the US Chamber of Commerce and the cheap labor lobby when it comes to border security—they want to assure a steady stream of near-slave labor for their donors), this crisis needs to be met with the full force of the Commander-in-Chief’s war-waging powers.

For the fullest explanation of that approach, read this piece from Ann Coulter. Coulter is a controversial figure, but I think her assessment of the Constitution is accurate here.

I find “national emergencies” and broad applications of presidential powers constitutionally distasteful; however, a core responsibility of the executive is to execute the laws, including immigration laws, and to protect and guard national borders. If Congress won’t pony up for border security, President Trump must use every power at his disposal as Commander-in-Chief to defend the nation. That’s pretty much his entire job!

Well, it looks like this post was as long as any other. I type pretty quickly when I’m in rant-mode, and nothing gets me there faster than illegal invasion.

Godspeed, President Trump. Please be more attentive to this issue going forward—it’s why we elected you!