Last night, President Trump nominated Judge Brett Kavanuagh to serve on the Supreme Court to fill the vacancy left by the retirement of Justice Anthony Kennedy. As such, I thought it would be germane to explore briefly the role of the Supreme Court.

Popular understanding of the Court today is that it is the ultimate arbiter and interpreter of the Constitution, but that’s not properly the case. The Court has certainly assumed that position, and it’s why the Supreme Court wields such outsized influence on our political life, to the point that social justice snowflakes are now worried about Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s diet and exercise regimen.

Properly understood, each branch—the President, the Congress, and the Court—play their roles in interpreting the constitutionality of laws. Indeed, President Andrew Jackson—a controversial populist figure in his own right—argued in his vigorous veto of the Bank Bill, which would renew the charter of the Second Bank of the United States, that the President had a duty to veto laws that he believed to be unconstitutional.

Unfortunately, we’ve forgotten this tripartite role in defending the Constitution from scurrilous and unconstitutional acts due to a number of historical developments, which I will quickly outline here, with my primary focus being a case from the early nineteenth century.

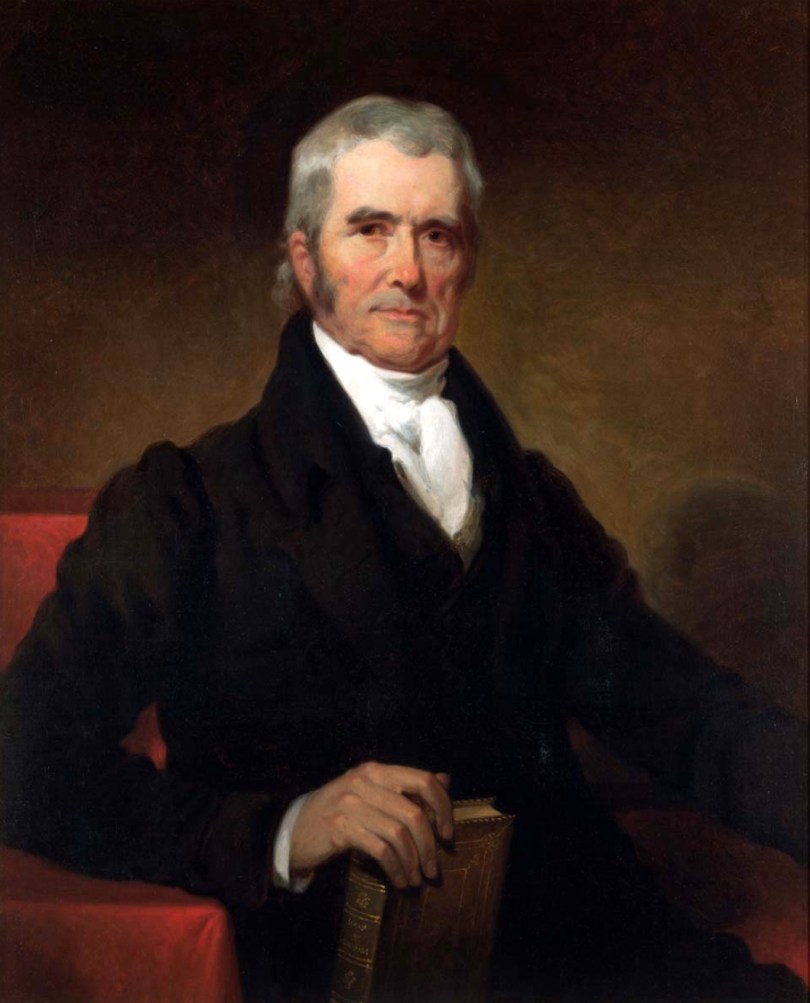

The notion that the Supreme Court is to be the interpreter of the Constitution dates back to 1803, in the famous Marbury v. Madison case. That case was a classic showdown between Thomas Jefferson and James Madison on one hand—representing the new Democratic-Republican Party in control of the executive branch—and Chief Justice John Marshall, a Federalist appointee, on the other.

The case centered on an undelivered “midnight appointment” of William Marbury to serve as Justice of the Peace for Washington, D.C. The prior president, John Adams, had issued a handful of last-minute appointments before leaving office, and left them on the desk of the incoming Secretary of State, James Madison, to deliver. Naturally, Jefferson and Madison refused to do so, not wanting to pack the judicial branch with any more Federalists, and Marbury sued for his appointment.

If Marshall ruled that Madison must deliver the appointment, there was a very real risk that the Jefferson administration would refuse. Remember, the Supreme Court has no power to execute its rulings, as the President is the chief executive and holds that authority. On the other hand, ruling in Madison’s favor would make the Court toothless in the face of the Jefferson administration, which was already attempting to “unpack” the federal courts through acts of Congress and the impeachment (and near removal) of Justice Samuel Chase.

In a brilliant ruling with far-reaching consequences, Marshall ruled that the portion of the Judiciary Act of 1789 that legislated that such disputes be heard by the Supreme Court were unconstitutional, so the Supreme Court could not render a judgment. At the same time, Marshall argued strongly for “judicial review,” the pointing out that the Court had a unique responsibility to strike down laws or parts of laws that were unconstitutional.

That’s all relatively non-controversial as far as it goes, but since then, the power of the federal judiciary has grown to outsize influence. Activist judges in the twentieth century, starting with President Franklin Roosevelt’s appointees and continuing through the disastrous Warren and Burger Courts, have stretched judicial review to absurd limits, creating “penumbras of emanations” of rights, legislating from the bench, and even creating rights that are nowhere to be found in the Constitution.

Alexander Hamilton argued in Federalist No. 78 that the Court would be the weakest and most passive of the branches, but it has now become so powerful that a “swing” justice like former Justice Kennedy can become a virtual tyrant. As such, the confirmation of any new justice has devolved into a titanic struggle of lurid accusations and litmus tests.

The shabby treatment of the late Judge Robert Bork in his own failed 1987 nomination is a mere foretaste of what awaits Judge Kavanaugh. Hopefully Kavanaugh is well-steeped in constitutional law and history—and will steadfastly resist the siren song of personal power at the expense of the national interest.