Congressman Mark Meadows (R-NC) dropped a bombshell earlier this week: Obama-era US ambassadors conspired with the Department of Justice against President Trump. Every site I find points back to the original Washington Examiner piece linked above, although the blog Independent Sentinel has a bit more commentary, tying it back to the fake Christopher Steele dossier.

You’ll recall the Steele dossier is a document the Clinton campaign commissioned through back-channels (a law firm), which was then used to obtain a FISA warrant to wiretap then-candidate Trump’s communications. That mendacious original sin spawned the odious “Russian collusion” narrative that lingers around the Trump Administration like a bad fart. Andrew McCarthy in National Review calls the dossier a “Clinton-campaign product.”

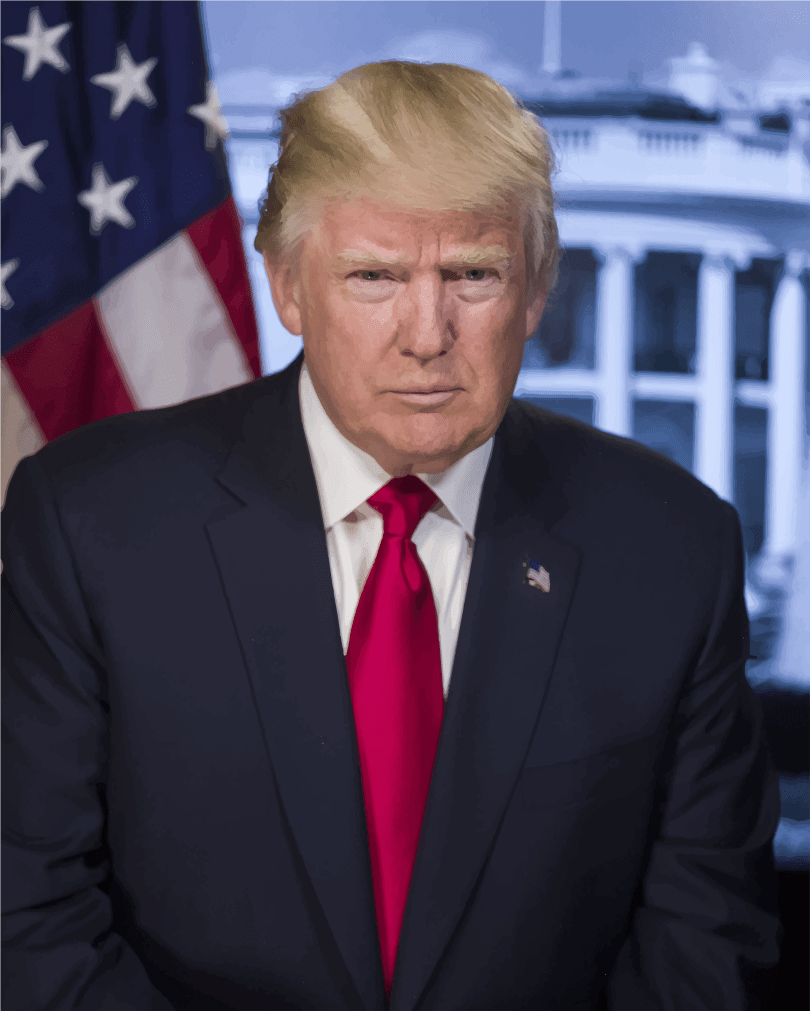

Regardless, if Meadows is correct, it serves as further proof that the Washington “Deep State”—the “Swamp”—is very, terrifyingly real. It will stop at nothing to disrupt President Trump’s America First agenda, and subvert a free and fair election.

What’s most chilling about all this chicanery is not that it targets President Trump particularly (although that certainly creates its own problems—few good, conscientious Americans will choose to run for public office, especially as conservatives, unless they have the cash and the guts to risk everything). Rather, it suggests that our experiment in self-government is dangerously threatened by a group of unelected elites cloistered in the Washington foreign policy and law enforcement establishment.

America stands at a crossroads. We’ve arrogated ever-more power to an unaccountable federal bureaucracy. Many conservatives—myself included—hoped that the extended government shutdown would aid in the draining of the Swamp. So far, though, it seems that the president is still surrounded by enemies.

We have a choice: we continue down the current road, ceding more power to the government, and hoping against hope for some kind of “enlightened, constitutionalist despot” to restore as much of our constitutional framework as possible. President Trump’s difficulties weeding out seditious bureaucrats suggest that path is incredibly difficult, and it will make presidential contests—as well as Supreme Court nominations—increasingly vicious. The progressive Left has an edge in the culture, the institutions, government, and on the streets.

The other option is weed out the federal bureaucracy, strike down the administrative state, and restore power to Congress. Restoring power to the States would also reduce the emphasis on national politics über alles.

But conservative politicians have been peddling those nostrums for years, without much headway. Thus, we find ourselves struggling along with a feeble Congress, a dictatorial federal court system, an arrogant administrative regime, and a presidency that is both excessively powerful and, paradoxically, unable to control its own bureaucracy.

Something has to give. President Trump has fought back ably overall, but one man alone cannot restore our constitutional order. Indeed, that’s the whole point of our system—to diffuse power broadly. He’s done what he could through the constitutional powers at his disposal.

I don’t know what the future holds, but if we want to continue the grand experiment in self-government, we have to hobble the Deep State—indeed, it must be destroyed.