On Tuesday, I wrote about the “Human Toll of Globalization“—the dire consequences, both economic and moral, that befall a community when its primary economic engine is gutted through a naïve faith in unbridled free trade and globalization. Another title for that piece might be almost a mirror of this essay’s from 2016: “Civil Society Needs Cash.”

I don’t want to take that argument too far, though. In the case of Danville, Virginia—and countless other American towns that have seen their prosperity flee abroad, or to bicoastal urban cloisters—a decaying economy wrought decaying morality, civil society, and civic pride. That would suggest that prosperity, in and itself, cannot sustain true morality and virtue.

Indeed, as I argue in the essay below, “Capitalism Needs Social Conservatism,” excessive prosperity and material comfort breed a kind of moral complacency, what Kenneth Minogue likened to widespread Epicureanism (an excellent essay, and well worth reading if you don’t mind subscribing to The New Criterion, which is also worth the price). Richard Weaver—one of my intellectual heroes—compared the material comfort of the then-mid-twentieth-century West to a drunk who, having grown addicted to alcohol, and requiring ever-greater quantities of it, no longer has the capacity to obtain the very substance he craves.

Milton Friedman famously argued that economic liberty is a necessary precursor to political liberty. Similarly, I would argue that morality and virtue are necessary pillars to sustaining economic liberty for any length of time. Indeed, George Washington argued that religion and public morality were “indispensable” to a self-governing republic.

In my mind, the orthodox libertarian (in the political sense, not the “free-will” libertarianism of the free-will-versus-determinism debate in modern philosophy) commits the same error as the orthodox Marxist in relying too much on economic analysis of behavior. The idea of the “rational man” or “man as a rational animal” is a uniquely modern concept, and while Westerners have tried hard to shoe-horn themselves into that mold, the inner, teeming depths of our souls are still pre-rationalist. We need God, and we still live according to symbols, rituals, and virtues.

As I wrote in 2016, “Without moral common ground and shared values that stress self-control, liberty rapidly turns to libertinism. Libertinism without a great deal of wealth leads to shattered lives, which in turn wreck families and communities.” I’ll explore these ideas further in my upcoming eBook, Values Have Consequences.

***

For the past week, I’ve written about the decline of the nuclear family, with follow-up posts about divorce and sex education, and about the negative impact of the of the welfare state on family formation. These post have generated some wonderful discussions and input from followers, and I’ve been surprised by their popularity.

As I wrote in “Values Have Consequences,” I’m devoting Friday posts to discussions of social conservatism. Social conservatism is increasingly the red-headed stepchild of the traditional Republican “tripod” coalition that also includes national security and economic conservatives (with the rise of Trump, populist nationalism could count as a fourth leg). Politically, this marginalization makes some sense, as it’s not likely that fifty or sixty years of cultural attitudes and values will be changed at the ballot box.

Nevertheless, social conservatism is an important leg of the tripod. Indeed, I would argue that the three coalitions are not at odds, but create logical synergies that allow each leg to stand. The stool is much more stable when the three legs work together.

Economic conservatism–by which I mean the belief that freer markets, fewer and lighter regulations, and lower taxes, or what is more properly called neoliberalism (after the classical liberalism of the 18th-century thinkers like Adam Smith)–is wonderful and hugely important. It’s led to massive gains domestically and globally, lifting untold millions off people out of poverty. It allows people to enjoy a greater variety of goods and labor-saving devices, and provides more leisure time (and plenty of things to do during that time).

But free markets unmoored from guiding principles, strong and stable institutions, and the rule of law can morph into mindless Mammon worship. Without a shared sense of trust and belief in human dignity, capitalism becomes cold and abstract.

Further, full-fledged economic liberalization without the limiting principles applied by constitutionalism and a morality supported by strong families and a robust civil society can lead to socially-destructive disruptions and behaviors.

As I’ve argued many times, making mistakes or bad choices is the necessary price of liberty. But for self-government to work effectively–and to avoid social instability–a healthy dose of social conservatism is the best medicine.

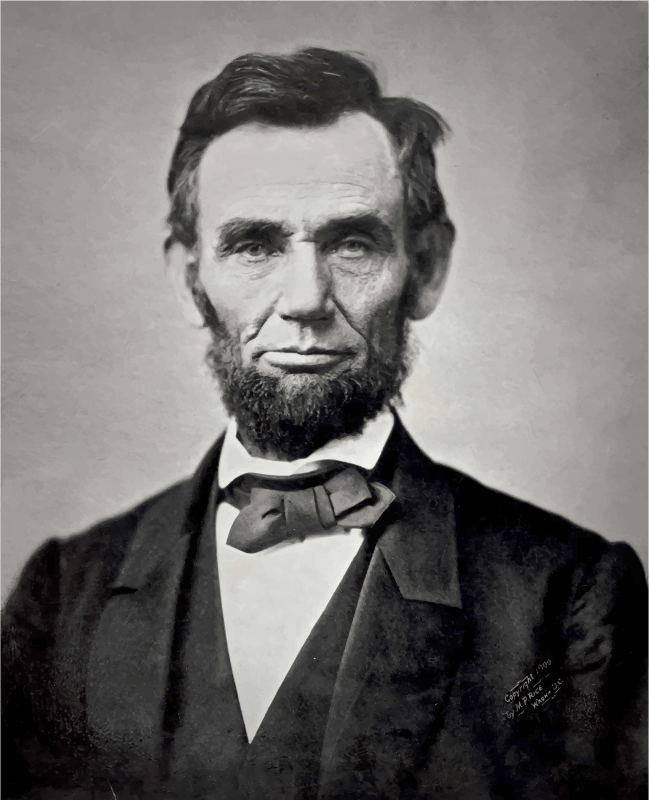

Former Arkansas Governor Mike Huckabee wears the most socially conservative outfit ever; later, he played bass on Fox News.

To offer an illustration from recent history, contrast the post-Soviet experiences of Poland (and most of Eastern Europe) with that of Russia. Despite decades under Communism–an ideology that was aggressively atheistic, stressing loyalty to the state and Communist Party over all else–Poland roared back into the West. It adopted neoliberal (modern conservative) economic policies, and was one of the few European nations not to suffer severely during the Great Recession.

Russia similarly adopted “shock therapy” after the Soviet Union collapsed for good in 1991. Rather than experiencing a huge economic boom, however, well-connected former Communists and others close to the old regime made off like bandits, leaving most Russians left holding the bag.

What’s the difference? For one, the Russians lived under Communism for nearly a generation longer than the Poles, meaning there were several generations of downtrodden, state-dependent Russians by the time the USSR collapsed. Many of these Russians were unable to adjust to a free-market system after living in a closed economy for so long.

Another key difference–and one that I think is extremely significant–is that Russians lost any scrap of civil society they might have possessed prior to the Bolshevik takeover in late 1917. Civil society–the institutions between the basic family unit and the government, like churches, schools, clubs, civic organizations, etc.–was automatically preempted when every club, organization, or activity became part of the Soviet government. The severely crippled (and, as I understand it, collaborationist) Russian Orthodox Church was unable or unwilling to push back against Soviet rule, providing little in the way of a spiritual alternative to the totalizing influence of Communism.

“[F]ree markets unmoored from guiding principles, strong and stable institutions, and the rule of law can morph into mindless Mammon worship.”

Poland, on the other hand, managed to maintain its deep Catholic faith. The Catholic Church as an international organization (and with powerful, influential popes, most notably the Polish anti-Communist John Paul II) could never be wiped out completely by Soviet Communism. Further, the Poles formed the Solidarity trades union movement, which offered an alternative to official Communist organizations.

Thus, after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Poland emerged with a strong civil society anchored in a richly Christian worldview and ethic. The shared sense of morality–one that stresses mutual respect, the dignity of human life, and the importance of honesty–allowed the complex deals and uptempo economic exchanges of capitalism to occur smoothly and rapidly. From these civil and religious values came a firmer grasp of and respect for the rule of law, making predictable economic activity and long-term planning possible.

Russia, on the other hand, devolved into a fast-paced, nationwide run on the national cupboard. Those with good connections grabbed whatever public funds and goodies they could. Normal Russians couldn’t figure out why their government checks and free lunches stopped coming, and couldn’t understand why (or how) to pay taxes. With the collapse of the Soviet Union, all civic organizations ceased to exist, because they were all part of the Soviet government. Without any civil society or other enduring institutions to model good behavior and to stress and enforce moral values, Russia struggled–and continues to do so–to adapt to global capitalism and democracy. Not surprisingly, they’ve turned to a dictatorial strongman for guidance.

***

What of the American context? As I’ve written before, I’m skeptical of full-fledged libertarianism–what I would broadly define as the marriage of economically conservative and socially liberal views–because it fails to acknowledge the need for strong moral values to uphold its own economic assumptions. Liberty and self-government can only really work when coupled with self-imposed order and restraint. Without moral common ground and shared values that stress self-control, liberty rapidly turns to libertinism. Libertinism without a great deal of wealth leads to shattered lives, which in turn wreck families and communities.

Eventually, unbridled, unchecked lasciviousness–even among (formerly) responsible adults–results in social chaos, requiring a dwindling number of hardworking, honest, and thrifty individuals to pay for the ramifications of poor moral choices that have been magnified many times over.

“[L]ibertarianism… fails to acknowledge the need for strong moral values to uphold its own economic assumptions. Liberty and self-government can only really work when coupled with self-imposed order and restraint.”

Capitalism’s blessing of unparalleled abundance is also a potential curse. Without a strong civil society that stresses good moral values–and without proper historical perspective–it becomes easy to take that abundance for granted.

That abundance also allows, for a time, more and more individuals to pay for the price of bad decisions. Prior to the modern era, few people were wealthy enough to risk the negative consequences of immorality. Now, Americans and Westerners enjoy a level of material comfort and well-being that can absorb at least some of the unpleasantness of questionable choices. Over time, however, that security breaks down.

Richard Weaver likened the situation to an alcoholic who is so addicted to his drink, he’s unable to do the work necessary to pay for his addiction. The more he needs the alcohol, the less capable he becomes of obtaining it. Likewise, the more individuals become addicted to luxuries, the less able they are to work hard to maintain them.

To avoid the fate of Weaver’s drunk, we must recognize the importance of social conservatism. While we should maximize individual liberty as much as possible, and within the bounds of the Constitution, we should also stress the moral and religious underpinnings that make that liberty both possible and responsible.