I’ve been out of town all weekend—thus yesterday’s very belated post—and it’s getting to the point in the academic year where all the craziness hits at once. That being the case, I’m posting another one of these “compilation” reference posts to give you, my insatiable readers, the illusion of new content. It’s like when a classic television show does a clip show episode: you relive your favorite moments from the series (or, in this case, the arbitrary theming I foist upon you).

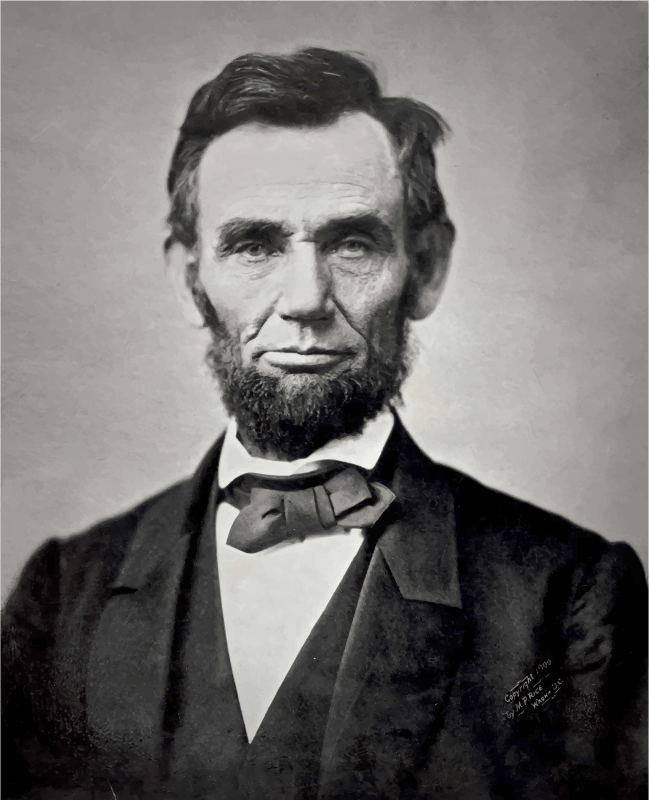

Today’s “Lazy Sunday” readings look back at my posts that pertain to President Abraham Lincoln, the Great Emancipator (read the first “Lazy Sunday” compilation). I noticed that I’ve been writing more about Lincoln over the past week (perhaps my quiet homage to the recently-completed Black History Month?), so I decided to compile, in one place, all of my Abraham Lincoln posts (at least, the ones I could find on this blog).

Without further ado, here are The Portly Politico‘s Lincoln Posts (in chronological order):

- “TBT: Happy Birthday, America!” – a reblog from the old TPP site, this post largely lets Lincoln speak for himself, as it features a full transcript of the Gettysburg Address. Always good for patriotic goosebumps.

- “Historical Moment – The Formation of the Republican Party” – this short post was adapted from a brief talk I gave to the Florence County Republican Party. The purpose of the meeting, I recall, was to focus Republicans on who we are as a Party and what we believe, so I thought it would be useful to give a brief introduction to the formation of the GOP. As the first Republican President (although not the first Republican presidential candidate—that honor goes to John Charles Fremont of California, who ran in 1856), Lincoln obviously exercised huge influence on the young party.

- “Lincoln on Education” – another “Historical Moment” adaptation (I’m all about recycling material), I was supposed to deliver this moment before a forum of candidates for the Florence School District 1 race in autumn 2018. I was all set to deliver it, but the FCGOP Chairman (accidentally?) skipped over me in the agenda, so I saved it until the following month’s meeting (again, why let good copy go to waste?).

- “Lincoln’s Favorability” – here’s one of TWO posts from last week about Abraham Lincoln. I’m going to give Lincoln a rest after tonight—he worked hard enough during the Civil War—but this piece looked at an interesting Rasmussen poll, that shows Lincoln is massively beloved by the American people.

- “Reblog: Lincoln and Civil Liberties” – this post is a reblog from Practically Historical, the blog of SheafferHistorianAZ. Sheaffer—a fellow high school history teacher—wrote a post detailing how Lincoln’s suspension of the writ of habeus corpus was, indeed, constitutional.

Happy Sunday!

–TPP