Monday’s post, “Symbolism and Trumpism,” looked at the importance of unifying symbols, and how our interpretations of those symbols derive from our local experiences. While Trumpism is a nationalist movement, it is one infused with localism—the more parochial form of federalism. Local identity—and rootedness to a place—is crucial in building investment in one’s nation.

Indeed, I would argue that localism is key to building a strong nation. People need personal and emotional investment in their communities. That means the ability to make a living and support one’s family where one finds oneself.

Unfortunately, we tend to emphasize the importance of national politics, while knowing very little about local and State politics—the level that can really affect our lives day-to-day. Yes, the federal government and its power are cause for concern, and we should keep a close eye on it. But the reason it’s grown to such gargantuan proportions is because we’ve delegated greater powers and responsibilities to it, rather than doing the hard work of governing ourselves and learning about our local politics.

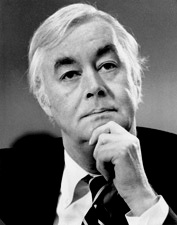

Yesterday was election day in Florence, South Carolina, and in other localities throughout the state. Specifically, there were a number of primaries, both Democratic and Republican, for various local and statewide seats, including an exciting State Senate race for my district, SC-31. That race saw a long-serving incumbent, Senator Hugh Leatherman, face challenges from local insurance agent Richard Skipper and current Florence County Treasurer Dean Fowler, Jr. This race was of particular interest because of the huge sums of money spent on it, as well as Governor Nikki Haley’s injection into the race (she endorsed Richard Skipper). Ultimately, Senator Leatherman retained his seat for another term (he’s currently been serving in the SC State House and/or Senate for thirty-six years) handily, with a respectable showing from Mr. Skipper.

(For detailed results of yesterday’s elections throughout the Pee Dee region, click here.)

For all that time, money, and effort, 10,953 voters cast ballots (according to returns from WPDE.com). In essence, those voters picked the State Senator (as there is no Democratic challenger, Leatherman will run unopposed to retain his seat in November). I don’t know the exact number of eligible voters in SC-31–it’s a strange district that includes parts of Florence and Darlington Counties–but I would wager there are far more than 10,953.

Turnout for primaries, especially off-season and local ones, is typically very low. Voters in these primaries tend to be more involved politically and more informed about local politics… or they happen to be friends with a candidate.

It’s often said that politics, like much else in life, is all about relationships. This quality is what gives local elections their flavor, and what keeps candidates accountable to their constituents. In other words, it’s usually good that we know the people we elect to serve us, or at least to have the opportunity to get to know that person.

Indeed, our entire system is designed to work from the bottom-up, not from the top-down. As I will discuss on Friday in a longer post about the concept of popular sovereignty (written in response to comments about last week’s post “American Values, American Nationalism”), this does not mean that we don’t occasionally entrust professionals to complete the people’s work–after all, I wouldn’t want a dam constructed by an attorney with no background in hydroelectric engineering. But it does mean that ultimate political authority derives from the consent of the governed–from “We, the people.”

In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, Americans often knew very little about the goings-on in the nation’s capital. Washington, D.C. was largely seen as a distant, almost alien place that served an important role in foreign policy and in times of national crisis, such as war, but few people followed national politics too terribly closely. Indeed, even presidential candidates were nominated by state legislatures or party caucuses, and were elected at conventions by national delegates (as opposed to the current system of “pledged delegates” that exists in conjunction with democratic primaries).

“[U]ltimate political authority derives from the consent of the governed–from ‘We, the people.'”

Instead, most Americans’ focus was on local and state politics, because those were the levels of government that most affected their lives.

Today, that relationship is almost completely inverted. Due to a complex host of factors–the centralization of the federal government; the standardization of mass news media to reach a national scope; the ratification of the XVII Amendment and the subsequent breakdown of federalism–Americans now know far more about national politics than they do local or statewide politics.

The irony is, the national government is where everyday people have the least influence, and where it is the hardest to change policy. Also, changes in national policy affect all Americans. What might work well in, say, Pennsylvania could be a poor fit for South Carolina or Oregon.

At the local level, though, Americans can have a great deal of impact–they can more easily talk to their city councilman than their congressman (although I would like to note that SC-7 Congressman Tom Rice is one of the most accessible and approachable people I’ve ever met).

Let’s follow the trends in dining and shopping and go local. Learning more about local politics is healthy for the body politic, and is one small but effective way we can begin to restore the proper balance and focus between the people, the States, and the federal government.