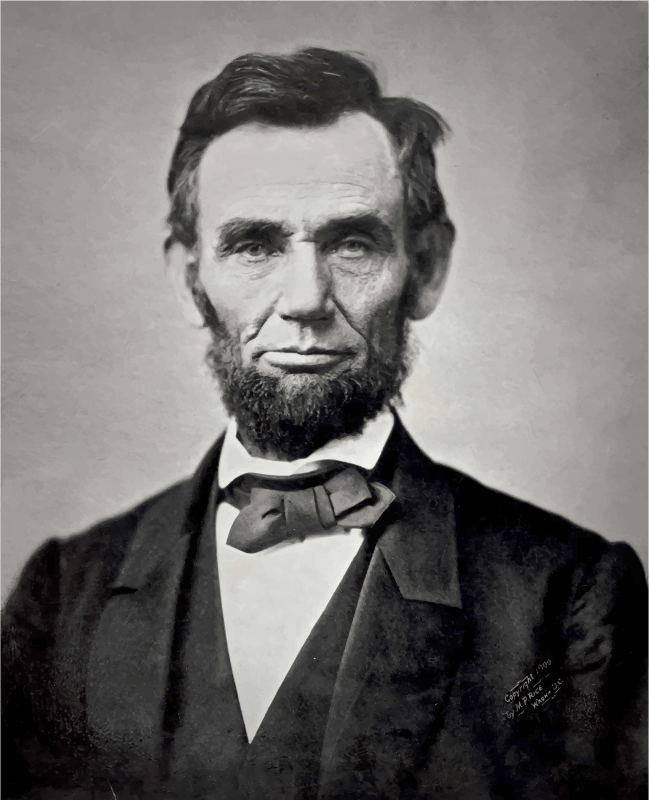

One of the joys of blogging is the opportunity to read the work of other writers in the “blogosphere.” Recently, I’ve been reading SheafferHistorianAZ‘s work at his blog, Practically Historical. Sheaffer writes brief, pithy posts about various historical figures and problems, and seems to have a particular interest in both Abraham Lincoln and Dwight Eisenhower, two of my favorite presidents.

Yesterday, he posted a piece entitled “Lincoln and Civil Liberties” that touches on an interesting constitutional question: did the Great Emancipator violate the Constitution when he suspended the writ of habeus corpus and arrested Americans without due process or the chance to see a judge?

Sheaffer argues that Lincoln was completely justified, as those arrested were actively seditious and traitorous. He cites the case of John Merryman, the Marylander arrested for his attempt to spur Maryland to secede from the Union. From Sheaffer (all links are his):

John Merryman was not an innocent victim… of government tyranny as portrayed by Chief Justice Roger Taney. Merryman led a detachment of Maryland militiamen in armed resistance to troops in Federal service. Taney was a partisan Democrat staunchly opposed to Lincoln and supportive of secessionist doctrine. Ex parte Merryman is not legal precedent at all and cannot be cited as such- it is a political document designed to hinder Lincoln’s attempts to protect Washington and preserve the Union. It was issued by Taney alone- scholars often make the mistake of assuming that the Supreme Court concurred with the ruling.

As Sheaffer points out, there is a trend in Lincoln scholarship that recasts the president as an out-of-control tyrant. The most prominent figure in this revisionist school is probably Thomas DeLorenzo, and the idea has circulated broadly, even if it hasn’t penetrated the American psyche (remember, Lincoln enjoys a 90% favorability rating among Americans today).

No doubt the American Civil War expanded federal powers, and indelibly changed the relationship between the States and the federal government, in some ways to the detriment of constitutionalism.

Consider that, prior to the Civil War, many States assumed they could “opt out” of the Constitution, having previously “opted in” to it. Lincoln argued that the Union predated the Constitution, and therefore could not be left; Daniel Webster earlier argued that the Union and the Constitution were “one and inseparable.”

Regardless, the American Civil War resolved by force of arms what could not be resolved in Congress or debating societies (of course, no political question is ever settled permanently). After that, the States would never have quite the same leverage over the federal government (probably for the better, but perhaps for the worse in some ways), and would lose even more with the ratification of the Seventeenth Amendment.

These are interesting questions to consider. Sheaffer’s contribution to this discussion is sober and direct.