Today’s #TBT looks back at an essay entitled “What is Popular Sovereignty?” It was a follow-up, of sorts, to “American Values, American Nationalism,” one of my most-read posts (a post that I still largely agree with, though I am moving away slightly from the idea of American as absolutely a “propositional nation”—I do think it was an outgrowth of a distinctly Anglo-American culture, though it’s proven remarkably adaptive as peoples of different nationalities and cultures have settled here). A friend posted a Facebook comment taking issue with the idea of popular sovereignty as I presented it in that essay, and this was my attempt to address his objections.

As I point out in the essay below, I do think we should have some un-elected positions within government. If the government is building a hydroelectric dam, I don’t want to hold an election for the lead engineer. I’m also not advocating for pure democracy, which the Framers of the Constitution rightfully saw as an odious and dangerous form of government that would, inevitably, collapse into mob rule and, ultimately, tyranny.

What I do warn against is the law-making power invested increasingly in the hands of an unaccountable federal bureaucracy, one that is technically under the control of the executive branch, but which functionally operates independently—the “Deep State,” as it were. If the President did have control over the bureaucracy, it would be bad enough—the executive would wield legislative powers. But an unaccountable bureaucracy that even the executive cannot rein in is even more frightening. At least we could hope for an “enlightened despot” executive who would minimize the damage of his bureaucracy, but if the bureaucracy runs itself, regardless of who holds the presidency, liberty is deeply threatened.

So, here is 2016’s “What is Popular Sovereignty?”:

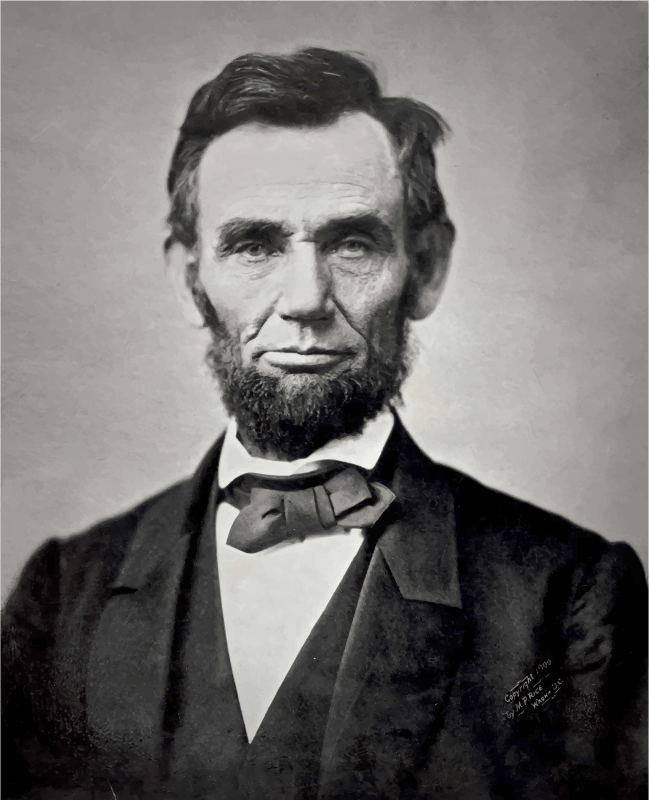

On Wednesday, 8 June 2016, I posted a piece entitled “American Values, American Nationalism.” In that piece, I discussed the “Five Core Values of America,” a set of values inspired by a government textbook I used to use with my US Government students. The second value, “popular sovereignty,” is deals with the idea that power in our political system ultimately derives from the people–as Abraham Lincoln said in the Gettysburg Address, our government is “by, of, and for the people.”

This post received quite a few comments on my Facebook page, including this one from a good friend of mine:

Now watch as I set my progressive-libertarian friend straight–respectfully.

My friend raised a very valid point: the Framers of the Constitution were suspicious, if not outright terrified, of democracy. Aristotle had identified democracy as one of the “bad” forms of government that came when rule by the people went bad. The Framers had seen the consequences of a federal government that was too weak, namely the barely-contained chaos of Shays’ Rebellion in 1785. Naturally, they wanted a government by, of, and for the people–thus the requirement that the Constitution be ratified by 3/4ths of the States in special ratifying conventions (designed to circumvent the Anti-Federalist state legislatures)–but they recognized that unbridled populism would lead to demagoguery. It’s pedantic to say it, but Nazi Germany is the quintessential example of a desperate people granting dictatorial powers to a charismatic individual.

“Pure democracy, without any checks on the majority’s power, quickly turns to one-man authoritarianism.”

The French political philosopher Montesquieu argued that the English government succeeded because it balanced monarchy, aristocracy, and democracy effectively, which further influenced the belief of the Framers that government should filter the will of the people through a complex system of checks and balances, and a rigorous, jealously-guarded separation of powers. Thus we have such institutions as the much-maligned (but quite brilliant) Electoral College, and a Senate that is designed to act as a break on the people’s (often fickle) will. Indeed, before it was corrupted by the XVII Amendment, the Senate was intended to represent the interests of the States themselves, rather than the will of the people, which is represented in the House of Representatives.

***

So, how did I address my friend’s concerns? Here is my reply (with some minor edits for clarity and brevity) to my friend’s remarks, and to elaborate on the concept of “popular sovereignty”:

You are correct in noting the skepticism with which the Framers viewed unbridled democracy. There was much wisdom in their skepticism, precisely out of concern that a well-positioned demagogue could, in the right circumstances, sway the fickle populous to his whims. Pure democracy, without any checks on the majority’s power, quickly turns to one-man authoritarianism.

When I write about popular sovereignty, then, perhaps it would be more accurate to say that I mean “consent of the governed.” The people consented through our constitutional order when they elected delegates to special state ratifying conventions (circumventing the generally Anti-Federalist-controlled state legislatures). The people, then, ultimately gave consent to that government, and continue to do so through regular elections. Of course, a complex system of checks and balances tempers the will of the people (voiced primarily through the House of Representatives, which controls the power of the purse), balancing with it the will of the States, and vesting a great deal of authority to halt dubious legislation in the hands of the executive.

As for Thomas Jefferson’s love of revolutions and his proposal to rewrite the Constitution each generation, the actual Constitution provides a useful mechanism that makes such rewrites generally unnecessary, but possible: the amendment process. So far, every proposed amendment has come from the Congress, and all but two have been ratified in state legislatures (the other two were ratified, like the Constitution itself, in special state ratifying conventions). However, the Constitution provides another method–one that has yet to be used–to propose amendments: 2/3rds of the States can convene a constitutional convention to propose amendments. Texas’s current governor, Greg Abbott, is currently working on just such a convention of the States. In short, the Constitution provides us a way to change it to fit current needs without throwing out the whole document.

Of course, I would argue strenuously for an originalist reading of the Constitution and its amendments, all of which should be read in the context of those who proposed them. This still allows for changes through the amendment process, and for congressional elaboration. The Constitution is not meant to cover ever eventuality, and gives a great deal of space to Congress and (this is important and often forgotten) the States.

“It approaches something like tyranny when the President has the power to write laws (indirectly through the bureaucracy he manages) and to enforce them.”

As for your comments about technocrats, perhaps I should clarify here, too. What I am primarily concerned about is the ability of federal agencies to write their own rules, many of which have the force of law. This practice is dangerous because most of these federal agencies operate within the executive branch and have little congressional oversight. Law-making powers are meant to rest solely within the Congress, and the job of the President is to duly enforce those acts to the best of his ability. It approaches something like tyranny when the President has the power to write laws (indirectly through the bureaucracy he manages) and to enforce them. Even scarier is the prospect that the federal bureaucracy has become so large that the President cannot exercise effective control over it, or even know what it’s doing! Many presidents–particularly our current one–have used bureaucratic rule-making to push unpopular measures without input from the people’s representatives. Congress is complicit in this, as it has delegated these powers to the executive bureaucracy, and the Supreme Court has allowed it to do so.

That being said, you are absolutely correct that there is a need for an intelligent, qualified, and motivated civil service, and, naturally, we want our dams to stay sealed tight and our roads to be paved and efficient. I would never dream of proposing we elect, say, the head of the South Carolina Department of Transportation. Here, again, the Constitution provides precedent: at the national level, the President appoints his cabinet heads, as well as federal and Supreme Court judges and justices. The Senate, however, has the responsibility of confirming these nominations, helping to prevent egregiously bad appointments.

If these proper checks and balances are maintained–if the different branches stick to their constitutional duties and limits, and if the proper relationship exists between the federal government and the several States–even a reckless executive can only do so much damage. If Congress vigorously protects its legislative prerogatives, an unqualified or authoritarian-minded president may still do some harm, but his ability to do so will be greatly diminished, and the damage can be contained.

***

This conversation went back and forth for a few more posts, which I will possibly include in future pieces. In the interest of space–as this rumination is already quite lengthy–I will refrain from sharing them now.

However, I would ask that you permit me one parting thought: we should be on guard against the lionization of the presidency. The Congress–which represents the people and is, therefore the seat of popular sovereignty–may be consistently unpopular, but it is the proper branch to resist the huge expansion of the presidency. Presidents increasingly attempt to speak for the people, but in a country that is divided between two entrenched, fundamentally incompatible political philosophies, it is nearly impossible to do so. Indeed, attempting to do so leads to a Rousseau-style attempt to impose “the common will” on people–whether they want it or not.

Instead, let’s speak for ourselves. We can do that through involvement in local politics, but also by communicating with our Congressmen and Senators. Let them know that we expect Congress to reclaim its proper legislative powers from the executive bureaucracy.