It’s a bit late to commemorate Independence Day (and I did it already on Saturday), but it’s #MAGAWeek2020 (read installments here, here, and here), and it seemed fitting to dedicate this edition of TBT to America’s Birthday.

I’m reblogging a reblog of a reblog from the old site. Last year’s post was “TBT^2,” or “TBT Squared.” Well, to be mathematically consistent, I had to square that square, which I think makes it “TBT^4,” or “TBT to the power of four.” I sure hope I’m right. Regardless, next year will be “TBT^16,” and so on.

I like the layer of commentary, like my piddling blog posts are Talmudic commentaries on other rabbinical commentaries (or, since I’m Christian, Biblical commentaries on other Biblical commentaries of the Bible). It’s interesting seeing how what’s changed over the years in this throwback posts.

For example, last Independence Day I had my first SubscribeStar subscriber. That was fun! I was also in New Jersey—one of the nicer trips I’ve taken. This year, it was a Southern Fourth, with lots of barbecue and hash.

On a more somber note, America has seen better days—but also far worse. I have to remind myself of that latter point, as it’s easy to get black-pilled and give into despair. It’s a commentary on the softness of my own life that today’s ructions—piddling when compared to conflicts of the past—seem insurmountable.

But even if America is on the rocks in some areas, God is still in control. We’re still the greatest country in the world, despite what the BLM and AntiFa ingrates think. To be quite frank, if they hate America so much, they’re welcome to move.

With that, here are past Independence Day posts:

“TBT^2: Happy Birthday, America!” (2019)

It’s Independence Day in the United States! God Bless America!

I hope everyone has been enjoying #MAGAWeek2019. Remember, you can read those full entries only on SubscribeStar with a $1/mo. or higher subscription. Your subscription also includes exclusive access to new content every Saturday, as well as other goodies from time to time.

I’m happy to announce, too, that I have my first subscriber. You, too, can support my work for just $1 a month (or more). That’s the price of a large pizza if you paid for it over the course of an entire year—you can’t beat that!

In case you’ve missed them, so far #MAGAWeek2019 has commemorated our second President, John Adams; our first Secretary of Treasury, Alexander Hamilton; and our national cuisine, fast food. You can also check out all of #MAGAWeek2018’s entries.

This Fourth of July I’m in New Jersey, and spent a great day yesterday at Coney Island in New York City. Despite not liking rollercoasters, I rode the historic The Cyclone, which was first constructed in 1927. I also visited the New York Aquarium, and tried a cheese dog at the original Nathan’s Famous hot dog stand, the one that will host America’s favorite hot dog-eating contest today. It was all quite touristy, but very fun.

To commemorate the Fourth of July, I’m reheating last year’s TBT feature, itself a reblogging of a classic Fourth of July post from 2016.

Enjoy your independence, and God Bless America!

–TPP

“TBT: Happy Birthday, America!” (2018)

Two years ago, I dedicated my Fourth of July post to analyzing Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address. In the spirit of MAGA Week 2018—and to preserve the TPP TBT tradition—I’m re-posting that classic post today.

A major theme of the blog posts from that summer was the idea of America as a nation, an idea I still find endlessly compelling. The election of President Trump in November 2016 has reinvigorated public debates about the nature of American nationalism, as well as revived, at least partially, a spirit of unabashed patriotism.

As a child, I took it for granted that America was a special place. When I learned American history as a child, I learned the heroic tales of our Founders. While revisionist historians certainly have been correct in pointing out the faults of some of these men, I believe it is entirely appropriate to teach children—who are incapable of understanding such nuance—a positive, patriotic view of American history. We shouldn’t lie to them, but there’s nothing wrong with educating them that, despite its flaws, America is pretty great.

“Happy Birthday, America!” (2016)

Today the United States of America celebrates 240 years of liberty. 240 years ago, Americans boldly banded together to create the greatest nation ever brought forth on this earth.

They did so at the height of their mother country’s dominance. Great Britain emerged from the French and Indian War in 1763 as the preeminent global power. Americans had fought in the war, which was international in scope but fought primarily in British North America. After Britain’s stunning, come-from-behind victory, Americans never felt prouder to be English.

Thirteen short years later, Americans made the unprecedented move to declare their independence. Then, only twenty years after the Treaty of Paris of 1763 that ended the French and Indian War, another Treaty of Paris (1783) officially ended the American Revolution, extending formal diplomatic recognition to the young United States. The rapidity of this world-historic shift reflects the deep respect for liberty and the rule of law that beat in the breasts of Americans throughout the original thirteen colonies.

America is founded on ideas, spelled out in the Declaration of Independence and given institutional form and legal protection by the Constitution. Values–not specific ethnicity–would come to form a new, distinctly American nationalism, one that has created enduring freedom.

***

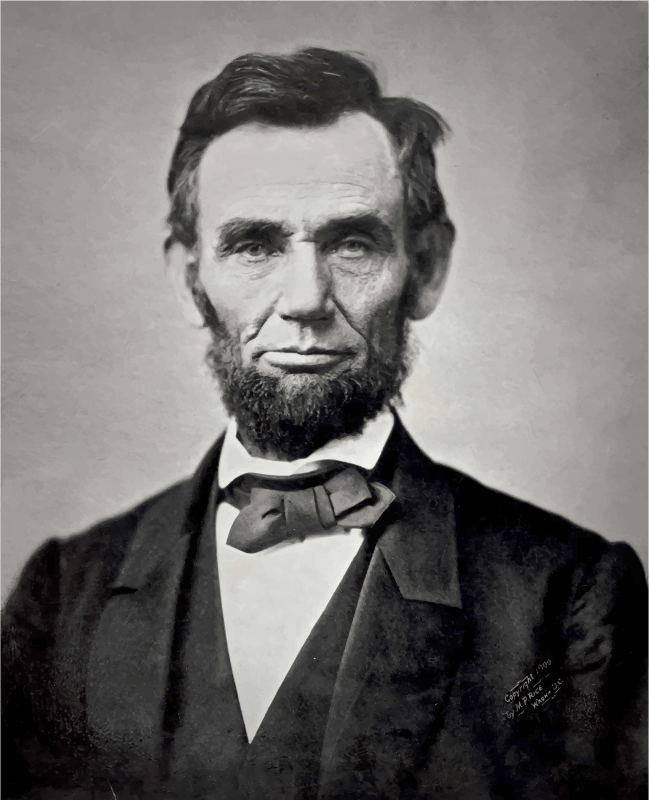

Rather than rehash these ideas, however, I’d instead like to treat you to the greatest political speech ever given in the English language. It’s all the more remarkable because it continues to inspire even when read silently. I’m writing, of course, about Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address. Here is the transcript (

Source:

http://www.gettysburg.com/bog/address.htm):

“Four score and seven years ago, our fathers brought forth on this continent a new nation: conceived in liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.“Now we are engaged in a great civil war. . .testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived and so dedicated. . . can long endure. We are met on a great battlefield of that war.“We have come to dedicate a portion of that field as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

“But, in a larger sense, we cannot dedicate. . .we cannot consecrate. . . we cannot hallow this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here have consecrated it, far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember, what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced.

“It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us. . .that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion. . . that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain. . . that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom. . . and that government of the people. . .by the people. . .for the people. . . shall not perish from the earth. “

***

The Gettysburg Address is elegant in its simplicity. At less than 300 words, it was a remarkably short speech for the time (political and commemorative speeches often ran to two or three hours). Yet its power is undiminished all these years later. President Lincoln was only wrong about one thing: the claim that the “world will little note, nor long remember, what we say here” has proven untrue.

I will likely write a deeper analysis of the Address in November to commemorate its delivery; in the meantime, I ask you to read and reread the speech, and to reflect on its timeless truths.

God Bless America!

–TPP